The Story of Loco Studios | Running a recording studio in the 1980s and 1990s

Nick and Jane Smith buy a house in Usk and move out of Plas Llecha. They keep on tenancy of Plas Llecha (from Robin Dean) and sublet to friend/artist/journalist Gerry Thurston. Gerry moves out and Nick and Roger Grey (ex Krisis/Casuals drummer who Nick has been playing with for some years) decide to set up a simple 8-track recording studio. Loco Studios opens…

Nick Smith was co-owner and technical manager of Loco Studios.

Nick Smith: When I was the guitarist in the Great Crash and other bands in the 70s I was just as interested in recording as in playing and writing. In 1979 I started to think about opening a studio with Roger Grey, a friend and drummer in a couple of bands I was playing in at the time.

In 1978 my partner Jane and I left Plas Llecha – the crumbling Welsh mansion which had been home to the Great Crash – to move into a normal house in nearby Usk. But I kept on the lease, and in 1981 Roger and I started up Loco Studios. We would both be engineers/producers and I was going to be responsible for tech while Roger looked after the business side.

Starting up

Initially it was a very primitive setup but we were busy from the start as the Tascam Portastudio had only just been invented and local bands were desperate for somewhere cheap to record. Our first customers were Cwmbran band The Refreshers and Newport’s The Perfectors (later to evolve into 60ft Dolls and Dub War).

The first multitrack recorder was a 1” Cady 8-track (built in a garage by enthusiast constructor Steve Waddy) used in tandem with a Dynamix 12 channel mixer and various other bits of kit. One of the Cady’s many unendearing features was that it lacked even a rudimentary tape counter or timer. This caused an early and near-fatal (for the engineer) disaster – the unintentional erasure of a completed song in a demo session with The Damned’s Paul Gray.

However, flush with the cash from almost back-to-back demo sessions, the Dynamix was soon replaced with a 24 channel M&A desk. One of the main motives for this purchasing decision was that the M&A offered more knobs to the pound sterling than its competitors. But we started to worry when the large and alarmingly flimsy console was delivered from Romford strapped to the roof of Mick and Alf’s (M&A) battered Volvo estate.

Welsh bands, TV and film

In 1982 Myfyr Isaac, a Welsh guitarist (ex Budgie), songwriter and producer became interested in Loco as a possible studio for the growing number of commissions he was getting to write and record TV music and produce Welsh artists. Myf didn’t seem too worried by the fact that Roger and I were making it up as we went along – we realised later that he knew far more than we did and probably thought we could be educated in the finer aspects of recording practice. But he was adamant that the Cadey 8-track and the M&A mixer had to go.

A quick visit to Don Larking’s magic equipment store in Milton Keynes provided a Tascam 16-track recorder (1” tape with dbx noise reduction) and an Allen & Heath 24 channel in-line desk. Myf also persuaded us to invest the then huge-for-us sum of £4k on the then state-of-the-art AMS RMX-16 digital reverb unit. This was the start of a long history of spending any short-lived profits on new kit to satisfy the whims – or imagined whims – of the record producers who make the crucial decisions on which studio to use.

In 1985 Myf Isaac and Caryl Parry-Jones wrote and organised ‘Dwylo dros y mor‘ – the Welsh Band Aid single. Roger Grey was the engineer for the sessions and the backing track was recorded uneventfully by Myf’s regular crew of Graham Land (Lar) drums, Graham Smart keyboards and Chris Childs bass. A few days later the entire Welsh rockocracy, HTV (the Welsh TV company) film crew, press, caterers etc descended on Loco on a frozen snowy day in February to record the many singers and to film the whole process. After about an hour the ancient transformer supplying electricity to the building exploded under the strain. Disaster was averted by HTV’s PR chief calling his counterpart at the electricity company – a fleet of engineers arrived to replace the entire installation and we were up and running again in less than 2 hours.

Expanding the team

The mid and late 1980s were good times for Loco. Daytimes were mostly booked by television and film companies for various music projects and by Welsh record companies for albums produced to satisfy the fast-growing demand for Welsh language music products.

I engineered many of these projects as Roger decided to step back from that role. He did however continue to take the lead in producing the few bands we invested in because we thought they might have a future (they never did) and in our jingles business, which flourished for a short time when local radio started up.

We therefore asked Cardiff musician Tim Lewis (now better known as keyboard maestro Thighpaulsandra) if he’d be interested in working as a house engineer at Loco. Tim started by taking the night shift – working after the daytime clients went home with self-financing bands or on his own production projects, including Rachel Stamp, Temper Temper and Tiger Tailz.

We also started to employ a long series of ‘tape ops’ – assistants who worked long hours for little money making tea, setting up mics etc and – possibly – learning something about the recording process. The first of these was Geraint Farr, who eventually left when his band The Darling Buds started to attract attention. Next up was Jon Lee, who also left when his band, Feeder, started to achieve real success. Others followed, but the only one who went on to carve out a career in pro audio was Dave Roden, who became The Stereophonics’ long-standing (and still current) front-of-house sound engineer.

The Allen & Heath mixer and the Tascam recorder were replaced in 1986 by a Trident TSM desk and a terrifying 3M 24-track recorder (fastest wind speed of any 2” recorder, tape path went through 180 ° as it passed around the front roller, no clamps to hold down the heavy 2” reels). The Trident was a fantastic console, but reliability became a problem and it was eventually replaced by an Amek G2520.

Noise reduction

A constant issue when recording with analogue media (ie tape) was high frequency noise, or hiss. It’s inherent in the technology, but later brands of tape (eg Ampex 456) did a lot to counter the problem by allowing you to record a higher level of signal. Other things, like correctly lining up tape machines are also essential for good signal to noise performance.

It’s the quiet sounds that are the problem, so pro audio companies Dolby and dbx both developed noise reduction systems designed to boost low level signals when recording by compressing them in several frequency bands and then re-expanding them to their correct levels on playback.

The 16-track Tascam had the dbx noise reduction system built in. This was essential for that format, as without it the signal-to-noise performance of the narrow track width (16 track on 1” tape) would have been unacceptable. The dbx system was powerful but it was thought by many to mangle the signal by losing crucial transients and high frequency response.

When we moved to the industry 24 track on 2” standard we normally worked without noise reduction systems. Recording at 30 ips (inches per second) rather than 15 ips gives better performance, including signal-to-noise, but at a premium – a 2” reel would only last for 15 minutes at 30 ips and even in those days cost around £75 a reel. On some multi-studio projects we had to hire in a rack of Dolby B noise reduction, but we generally abided by the Spinal Tap tenet that ‘you can’t record metal with Dobly’.

Synchronising audio tape to picture

In the 1980s Loco did a lot of work on film scores and other music-to-picture commissions. In those pre-digital times it wasn’t an easy matter to get audio to sync to picture.

Initially, we used an Audio Kinetics Q-Lock Synchroniser. The Q-Lock would read timecode from a Umatic working copy of the picture and from track 24 of the multitrack recorder, and constantly controlled the multitrack’s capstan motor so that the audio ran in sync with the picture. This generally worked OK in play mode, as long as there weren’t too many dropouts on the timecode track. But winding forwards or back meant the Q-lock had to guess the relative positions of the Umatic and the multitrack by using the very approximate tape counter information, augmented by occasional ‘sniffs’ of timecode obtained by momentarily bringing the 2” tape into contact with the heads. Often the guessed position was wildly inaccurate, causing abrupt (and, with the 3M, scary) changes of tape direction as the multitrack was brought by the Q-Lock to the desired location.

Later we changed to the more advanced Timeline Lynx synchroniser, which together with a Studer A800 multitrack, gave a more relaxed and predictable user experience.

The 1990s

As the 1980s came to an end a lot of our Welsh music producer clients were building their own studios and using fewer live musicians. This was partly a result of better and cheaper recording & MIDI technology and partly because of reduced budgets from TV and film production companies. The improvements we’d made to the studio meant that Loco’s rates were now too high for many private customers, so we had to start looking elsewhere for work. And the only elsewhere available was English record companies. We realised we would need to provide a residential facility, and estimated that there was a good market to be exploited for lower budget albums – bands who were either on the way up or on the way down. We converted a loft into a flat for the producer and engineer, and a barn into a cottage for the band. Nowhere near as luxurious or spacious as Rockfield or The Manor – but our day rate was a lot lower.

The strategy seemed to work and early residents at the studios included Julian Cope, Shed Seven, The Levellers and The Sawdoctors (the last two with producer Phil Tennant).

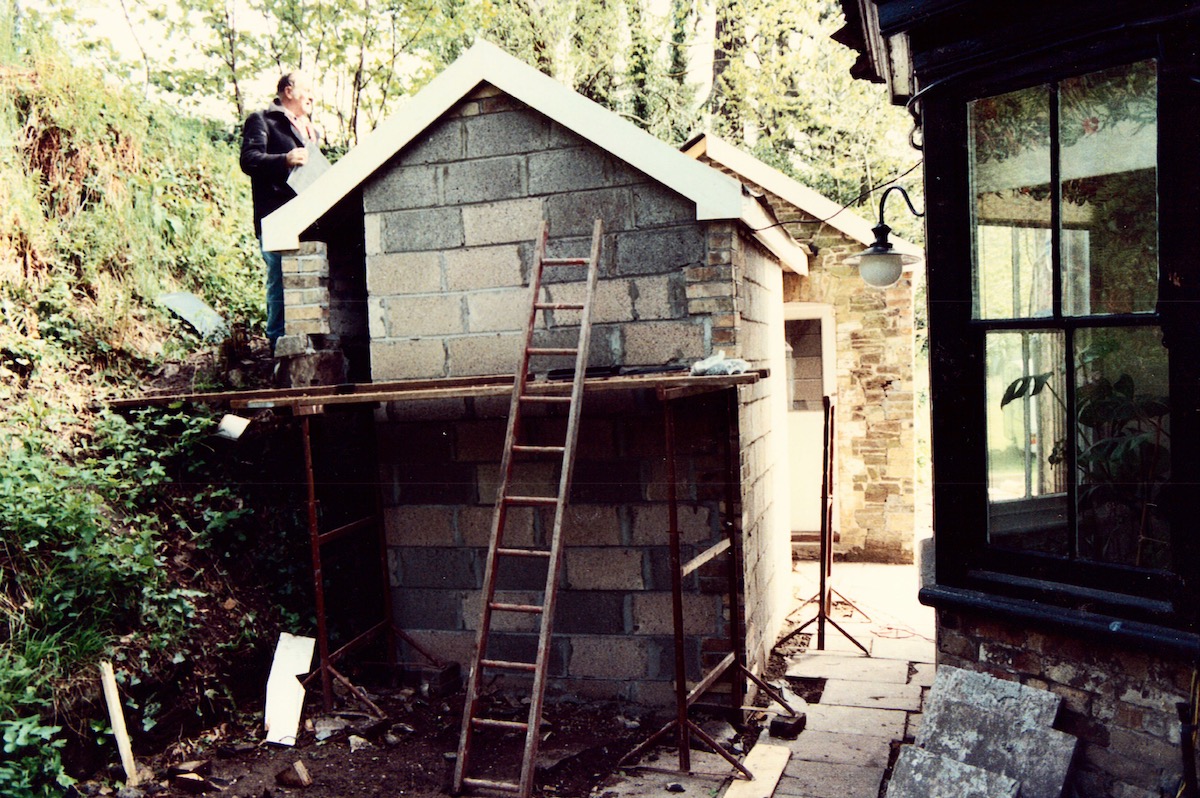

In 1992 we carried out a major rebuild. The control room was doubled in size, the floor above converted to a large kitchen & lounge and the office & workshop moved to a new outbuilding. The new control room was designed by Recording Architecture and built by in-house carpenter Alan Reardon’s team under RA’s direction.

At the same time we replaced the Trident TSM with an Amek G2520 mixing desk and the 3M 24-track recorder with a Studer A800 purchased from Pink Floyd’s Britannia Row studios.

In 1994 the Studer A800 MkI was replaced by a Studer A800 MkIII bought from Howard Jones.

Maintenance

Loco was always run on a shoestring. I was responsible for maintaining and installing all our kit and systems but we also depended on nearby Rockfield Studios’ legendary maintenance engineer Otto Garms. Even in later days Rockfield was a step up from us in the pecking order but we always had a very friendly and co-operative relationship with them. When the Stone Roses had to temporarily leave Rockfield (having been there for the best part of a year) they came to Loco for 2 weeks to continue work on their second album. We also helped each other out with equipment loans and tape stocks.

But it was Otto’s unfailing help and patience that was the most important part of the relationship. He could mend anything, knew all there was to know about Studer recorders and Neve desks, and never complained about being asked to turn out in the middle of the night (which was when serious equipment failures always seemed to occur).

Owen Morris’ first visit to Loco was to produce an album with Cambridge band The Bible (band members included Boo Hewardine and the McColl brothers).

He subsequently returned to the studio to produce albums with bands including Ash, The Verve and Oasis. At his urging we (reluctantly) decided to upgrade the mixing desk.

The two big desk manufacturers at the time were Neve and SSL. Rockfield had a Neve (and also an MCI in their Courtyard Studio) and Otto Garm’s knowledge of big consoles was therefore Neve based. I generally followed Otto’s advice but on this occasion Owen Morris’ enthusiasm for the SSL – because of its reputedly harder-edge sound (the Neve was thought to be more ‘musical’) – overcame Otto’s reservations. In 1994 the Amek G2520 was replaced by an SSL 6048E 48 channel mixing console bought for around £70k from BBC Bristol.

Roger and I started to share these misgivings when we discovered the rates charged by SSL specialist technicians. And by the time we finished what turned out to be the massive job of commissioning the SSL – Tim and I spent 2 weeks under the new desk crimping an estimated 3,000 pins and inserting them into multiway connectors – I was beginning to think we might have made a costly mistake! But eventually the new desk was up and running and settling into its planned function of pulling new work into the studio.

Money

Assuming you can fill the diary, the major financial concern for an independent recording studio is cash flow. In the 1980s we lived in clover – our major daytime client, HTV, paid a good rate and always settled their invoices on time. And the steady stream of bands using the studio at night and at weekends generally paid cash.

But things were different once our client base became record companies. Confirming a pencilled-in booking was the first difficulty. Some record companies would parallel book more than one studio, delay signing the contract and then ring up just a few days before the start to either cancel or demand a rate reduction. The problems didn’t end once the band were settled in because the people using the service (the producer and band) were not the people paying the bill (the record company). So we couldn’t risk incurring expenses such as booking session musicians or hiring equipment without faxed approval from the record company.

Once the session was over the real struggle began – getting paid. This usually involved many reminders and phone calls – it was almost unknown for a record company to pay within the agreed settlement period. On one or two occasions the record company went into liquidation, leaving our bill unpaid. The worst was when Rough Trade went bust in 1991 owing us around £10,000, which nearly forced Loco into bankruptcy as well.

Co-owner Roger Grey was a genius at managing Loco’s finances – constantly restructuring loans, getting grants to improve property, chasing record companies for money, putting off settling with our creditors for as long as possible – and eventually managing the sale of the studio to Asia in 1996.

The final two years

In 1995 Loco failed to get the second Oasis album (Rockfield got the job), which was a wake-up call to the fact that, no matter how much money we spent on kit and services, the buildings at Loco just didn’t have enough space or class.

At the same time, we started to have a lot of problems with certain ‘indispensable’ clients and the level of damage and mayhem they were creating.

We felt that, while wrecking hotel rooms might be accepted behaviour for prima donna rock stars, trashing studios was a bridge too far. Episodes included: finding photos of a member of a certain band dancing (luckily in bare feet) on the mixer faders (a testament to the SSL’s robust construction), a leather/chrome chair being thrown through the control room window, and opening up one morning to find a Yamaha NS10 (small near-field monitor speaker) embedded in the cone of one of the main monitor speakers.

So, in 1996 Roger and I decided we’d had enough and set out to find a buyer for Loco.

After several visits and negotiations with bassist John Payne, Loco was sold to Asia. The sale included the business and all the equipment, but not the freehold – Plas Llecha continued to be leased from the owner of the property.

After

On the day in May 1996 when a massive truck containing Geoff Downes’ vast collection of keyboards arrived outside the studio and we heard that the purchase had been completed I only had one emotion – relief.

I’d barely touched a fader since we’d become a ‘dry hire’ facility – one where producers normally brought their own engineers, although quite a few did use the excellent Tim Lewis. Roger Grey and I both had other interests by this time and our increasingly distant involvement with Loco had largely become the unrewarding tasks of managing cooks, cleaners, maintenance and budgets.

Roger and I were both happy to move on and it was great that we were able to sell the studio as a going concern.

In fact, we owed those problem customers a debt of gratitude. The studio business became even more competitive and unprofitable in the 2000s as digital kit became cheaper and better and more and more bands spent their advances and royalties on building their own facilities.

Asia stayed at Loco until the mid-2000s and Tim Lewis continued to occasionally engineer for them.

Some clients/artists – in rough chronological order

The Refreshers, The Perfectors, Paul Gray (The Damned), Myfyr Isaac, Caryl Parry-Jones, HTV, S4C, Golley Slater Advertising Agency, Huw Chiswell, Geraint Griffiths, Geraint Jarman, Mark Thomas, The Lost Famous, Ar Log, Yr Hwntws, Tiger Tailz, Rachel Stamp, Brian Breeze, Danny Chang, Micky Gee, RAK Records, Siriol Animation, Fireman Sam, Charlie Barber, Frevo (Dylan Fowler), Hennessy Lawson, Chris Winter, Endaf Emlyn (music to several films), Jet Harris, The Levellers, The KK Band (Iceland – Bjork sang on one track), The Sawdoctors (2 albums), Dub War, Any Trouble (Clive Gregson), The Bible. Julian Cope, The Boo Radleys, Ash, Shed Seven, The Mission, Earache Records, Bolt Thrower, Stereo MCs, Jethro Tull, The Verve (‘A Northern Soul’ recorded & mixed), The Stone Roses, Oasis (‘Definitely Maybe’ vocals, overdubs, mix).

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Plas Llecha (1976) | Photograph: Nick Smith

The Great Crash | Interview | Lost Recordings: ‘Deadfire Echoes’

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Automotive / EVs, Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- BlockOffsets. Modernizing Environmental Offset Ownership. Access Here.

- Source: https://www.psychedelicbabymag.com/2023/08/the-story-of-loco-studios.html