We are pleased to bring to our readers this guest post on genus-species patent disputes in India by Dr. Victor Vaibhav Tandon. In this post, Dr. Tandon discusses Delhi High Court’s position on genus-species patents over different cases and assesses what could be the future course for the patentees in disputes involving such cases. Dr. Tandon is an academician turned lawyer, with the law firm Saikrishna and Associates. He continues to teach patent law- rather sporadically- at ILI and ISIL. The views expressed herein are strictly personal. He was not involved in any of the cited matters in any manner. He is grateful to DU and ILI for nurturing free-thinking and critical appreciation- when he was a student there, and to the firm for creating an atmosphere of free flow of ideas sans restrictions of hierarchies. He says that these are values that all institutions, of whatever type or field, must encourage.

Genus-Species Disputes: Where From Here?

By Dr. Victor Vaibhav Tandon

There was a sense of déjà vu. On 1st April 2013, the Indian Supreme Court had refused Novartis’ application for beta-crystalline form of Imatinib Mesylate as it failed the threshold bar of section 3(d) of the Patents Act (Novartis I see here). And more than a decade later, on 24th April 2024, a Division Bench (DB) of Delhi High Court overturned a single judge’s decision, thus rejecting Novartis’ request for interim relief against Natco Pharma in relation to Eltrombopag Olamine (IN 233161), basis, inter-alia, section 3(d) (Novartis II see here). In doing so, the DB- it is hoped- settled some aspects of genus-species patent disputes. It will be interesting how big pharma- the patentees- respond to this development, an aspect explored later in this piece.

The Understanding on Genus- Species Patents So Far

One could, simplistically, observe that Novartis I related to patentability (patent eligibility for purists), while Novartis II relates to an infringement action. But a deeper dive would lead one to agree with another DB of Delhi High Court (see Vifor v. MSN here), which has clarified that the tests/ standards of novelty applicable at stage of patentability and those for determining infringement cannot be different. Both at stage of grant (patentability) and while deciding infringement, the language of claim remains unaltered, and claims and specification do not change hues at the two stages, but remain static.

The interlude between Novartis I and Novartis II had seen another DB of Delhi High Court rule against AstraZeneca and deny its request for interim relief in relation to Dapagliflozin- see decision (Dapa DB). Patentees had consistently sought to distinguish Dapa DB from other genus-species disputes by arguing that AstraZeneca had asserted both genus and species patents therein- and that therefore Dapa DB was factually so different from every other genus-species dispute as to have no applicability to any other genus-species case at all! By such a simplistic strategic tweak, every patentee could avoid the albatross of the Dapa DB from being hung around its neck; until Novartis II DB had to state the obvious: “the fundamental question involved in both cases is whether a patentee can claim protective rights in respect of the same compound as covered under two product patents: one, a broad claim covering several compounds with an essential core, claiming to possess therapeutic value, and the second a specific claim, in respect of the compound in question”. Those familiar with genus-species disputes would recognize that the former is the genus patent and the latter is the species patent. Holding this, Novartis II aligned itself with Dapa DB, and went on to hold, inter-alia,

- There is no presumption of validity of a granted patent, which can be challenged any time in its life: Fact of examiners having conducted necessary investigations prior to patent grant does not render it immune from validity challenge- and such validity can be challenged at various stages. This should be another death knell for oft-argued ‘clearing the way’, borrowed from English jurisprudence (See, Smithkline Beechem v. Generics UK Ltd.– at page 11, line 11 to page 12, line 8.). In India, due to a Supreme Court decision, a defendant can very well choose to launch a counter-claim or a revocation when sued, and need not challenge a patent beforehand See, Aloys Wobben). Novartis II rejected the contention that since there is no pre-grant or post-grant opposition, Defendant has to cross a very high threshold to assail patent validity. And like Dapa DB did, Novartis II also rejected the contention that since suit patents were old, they should be presumed to be valid (a contention also rejected by a single judge of DHC in dispute related to Linagliptin and Linagliptin + Metformin, see below).

- Higher threshold set by Section 3(d): Section 3(d) sets a higher invention threshold in respect of medicines, drugs, and other chemical substances, which may be inventive but will remain patent ineligible if they are new form of a known substance with known and usual qualities, unless the efficacy of such new forms differs significantly from those of the known substance. Further, inherent properties- such as higher solubility or bioavailability of salt forms- would not be considered as enhancing therapeutic efficacy of a medicine/drug.

- Coverage- Disclosure Dichotomy: Importantly, the DB held that there cannot be a gap between coverage and disclosure- an argument done to death by patentees, who have consistently argued that Novartis I did allow for some gap and only disallowed a “vast gap” between coverage and disclosure. Novartis II held that there cannot be such a dichotomy and such dichotomy would negate the fundamental rule underlying the grant of patents. Patentees had hitherto argued, basis the alleged gap between coverage and disclosure, that while the species or the specific drug is covered within the genus, but it is not specifically disclosed in the genus patent, and that the specific disclosure and claiming of the species happen only in the species patent. Interestingly, Novartis II (see para 49) further noted, just like the Dapa DB, that both genus and species patents were not-statutorily defined concepts (a peculiar trait of Indian patent practice has been its rather bewildering propensity to borrow concepts like Markush claims from US practice.)

- Interpretation of disclosure requirements and compounds fully covered in first patent : Further, and this may have implications for interpretation of Section 53(4) of the Patents Act, Novartis II noted that “If the complete specifications furnished are compliant with Section 10 of the Act and the claim is valid, then it would follow that a compound, which is covered within the said claim is also included in the complete specifications. Thus, the second patent for such a compound that was fully covered would be vulnerable to challenge”. Section 53(4) states inter-alia that once a patent has expired, the subject matter covered by the said patent shall not be entitled to any protection. Interestingly, the provision uses the word ‘covered’, and not ‘claimed’ or ‘disclosed’.

Arguments and Conclusions- Again and Again and Again!

An interesting aspect of genus-species disputes is that neither the arguments nor the conclusions are new. In fact, even the questions and context are not new. For example, the following are passages from Novartis I and Dapa DB respectively- cases that some would argue are as different as Sun and Moon- but the law, the questions and the answers thereto are not different:

It would be apparent at once, from a reading of the above passages (and the judgments in general), that the patentees’ arguments have always proceeded on the basis that the genus covers but does not disclose the species, that patentee of the genus or anyone else could invent the species from the genus, but if someone else was to do so, such person would need approval from the holder of the live genus patent. Of course, in a high stakes battle, patentees and generics will not cede ground and both will re-agitate the same script ad infinitum. But with two Division Benches- and several single judges- of Delhi High Court now holding firmly against patentees/ big pharma, where do we go from here.

Where from Here?

Resort to Lobbying and the Threat of Unilateral Sanctions?

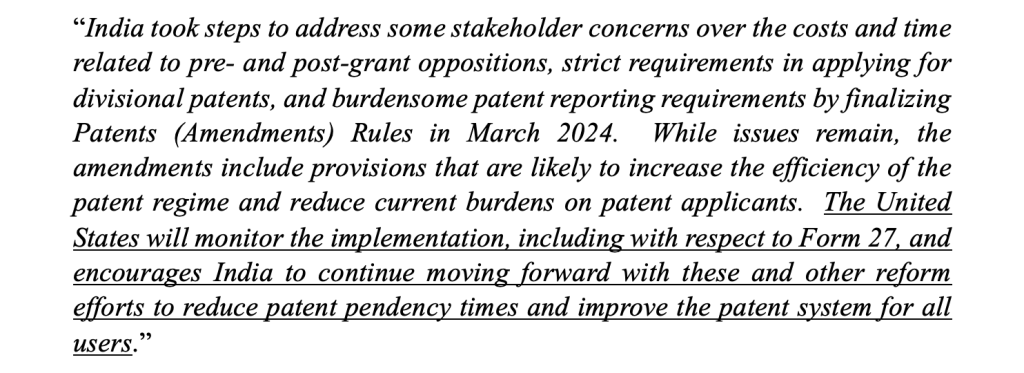

Firstly, big pharma could do what it has been doing for more than three decades with great effect- lobbying, right from the time of inclusion of TRIPS within the fold of WTO (this is too well researched and documented to be repeated herein) to the Special 301 Reports of US Trade Representative, which retains India on its priority watch list, and curiously notes in its 2024 edition that,

That US and big pharma always had problems with Indian Section 3(d) and compulsory licensing are an open secret. But for the special report to specifically state that US wants to monitor the situation regarding Form 27/ patent working requirements makes matters a bit too obvious (even when we accept that it is indeed US’s business to be concerned about patent laws of every other country!). For a hard-hitting and radical view of things in this context, see here. It will be interesting to see, if, and how, big pharma captures the narrative on genus-species disputes and pushes for reform(!) of section 3(d) and may be section 53(4) itself.

Exploring Other Fora?

Secondly, and the signs of this are already there- patentees could venture to other High Courts, forum shifting to get interim reliefs- including ex-parte orders (not a bad legal strategy at all, to be fair). For those familiar with genus-species disputes, Boehringer Ingelheim had approached the Himachal Pradesh High Court with unprecedented success (including, initially ex-parte orders) in relation to Linagliptin and Linagliptin + Metformin. It then came to Delhi High Court, only to suffer a refusal of interim relief (see here) with the Delhi High Court noting that “With the greatest respect, the aforesaid observations of Himachal Pradesh High Court are at variance with the findings of the Supreme Court in Novartis (supra) and the judgment of the Division Bench in AstraZeneca (supra). With due respect, I am not in agreement with the aforesaid view taken by the Himachal Pradesh High Court.” Interestingly the single judge in this matter was also part of the Dapa DB.

Most recently, Boehringer again secured interim relief against generics in relation to Empagliflozin on 30th May 2024, from the Himachal Pradesh High Court (see decision here). Interestingly, the same bench decided both the empagliflozin dispute and the earlier linagliptin dispute at the HP High Court. Obviously, Delhi High Court’s decisions hold mere persuasive value for other High Courts, and where facts are different, application of the same legal principles may lead to different results. Importantly, will other patentees follow in the footsteps of Boehringer, and explore other forums? And will the genus-species conundrum eventually reach the Indian Supreme Court?

Will There be a Conclusion?

It will be critical for the health of Indian patent jurisprudence to avoid a scenario where lobbying or forum shifting is allowed to lead to dilution of rigours and nuances of Indian jurisprudence. Further, it will be prudent to have some amount of consistency in application of tests as well as the interpretation of those tests- including what exactly is the credible challenge that a defendant must raise at the interim stage and whether there should be any place for public interest at all in patent jurisprudence (for development of law relating public interest in relation to pharmaceutical patent infringement and grant of interim reliefs, see the blog post here).

This author at least tends to believe that public interest must have some role to play in matters of interim relief in pharmaceutical patent law- because even where commercial entities are involved, there is a third stakeholder- the consumer or the public whose right to affordable healthcare may be demonstrably involved in patent matters. However, divergent views have come from benches within the Delhi High Court on place of public interest in context of interim reliefs in pharmaceutical/ agro-chemical patent litigation. The Himachal Pradesh High Court has noted in its Empagliflozin decision that “a commercial rival against whom there is an allegation of infringement of patent cannot be allowed to raise the plea of public interest” since there were checks and balances in Patents Act “to cater” to public interest. Hence, there is a need for some consistency of law in this area, as noted above.

And benches across the country will perhaps have to be alert- it is accepted within doctrine of separation that courts cannot enter the domain of legislation and policy making- but interpretation of law can be an important tool to steer jurisprudence in certain intended directions. The classic example is of constitutional law- where upon a conversation between Justice Frankfurter and B.N. Rau, ‘due process of law’ was dropped from Article 21, only for the concept to make an entry via Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India. However, not every interpretation and not every borrowing of alien concepts from other jurisdictions would turn out to be beneficial!

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- PlatoHealth. Biotech and Clinical Trials Intelligence. Access Here.

- Source: https://spicyip.com/2024/06/genus-specie-disputes-where-from-here.html