In a “Jhakaas” (a slang for fantastic) news for the actor Anil Kapoor, Delhi High Court granted the actor an interim injunction against use/ misuse of his personality rights. While the development is being extensively discussed in the context of interaction between personality rights and deepfakes (see here, here, here and here), we are pleased to bring to you a guest post by Dr. (Prof.) Sunanda Bharti on the copyright aspect of the personality rights emitting from this order, reserving a separate post for later on other interesting issues like use/ misuse of personality rights via deepfakes and application of doctrine of first sale in the context of NFTs. Prof. Bharti is a Professor of Law at the Delhi University, and her previous posts can be accessed here.

Image Rights Alright—But Can They Trump Established Rights and Doctrines? Should They?

Dr. (Prof.) Sunanda Bharti

The recent interim order issued by the Delhi High Court in Anil Kapoor v. Simply Life India and Others CS(COMM) 652/2023 is full of curiosities for two reasons which I would comment upon in the following paragraphs, after introducing the context.

Background

Through the suit, Anil Kapoor, a celebrity actor of the Indian Film industry maintains that he has 1) Personality rights, including right to publicity; 2) Copyright in his dialogues and images, 3) Rights at common law like the right against passing off, dilution and unfair competition.

Scope

I would like to focus my attention primarily to the copyright aspects of the personality rights so claimed. Personality rights are also known as image rights which aim to protect the commercial exploitation of myriad aspects of one’s psyche, identity and disposition. Meaning, if ‘X’ is a celebrity (say, a film star), his image rights are expected to create a safety net for him, allowing only him to control his image, name, and voice usage etc. Under Copyright Act, 1957 —most of these may come under the category of works in which copyright subsists. But, ‘safety’ against what? My submission is that it has to be safety against disparagement, dilution, advertising related passing off and offences of similar nature/gravity. It cannot be offered as an absolute right to control everything about one’s persona. Before bestowal, courts need to think, in appropriate cases, of rights of third parties, fair use covering mime, research/educational advancement, criticism and the like.

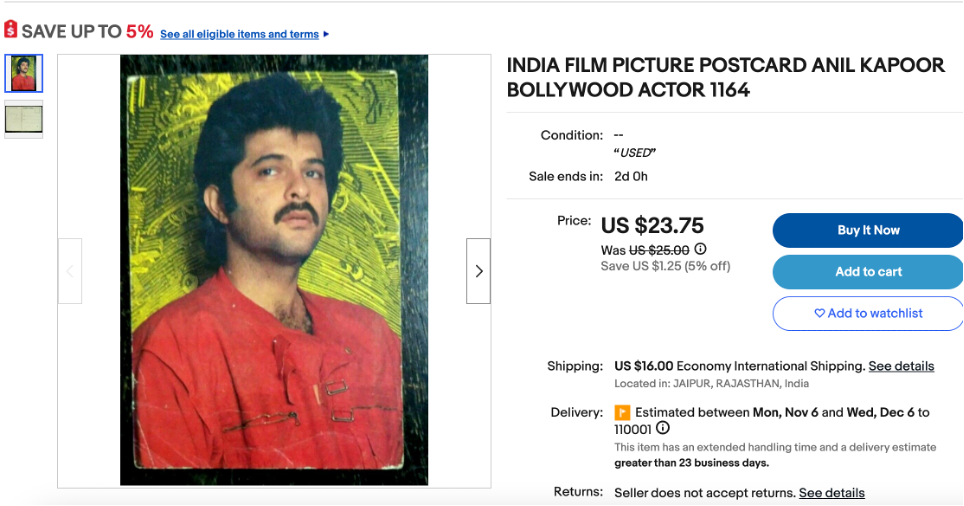

Image rights are new to India, as to most of the world. Hence, their vindication is sporadic and operates on a sketchy and fragile ground. Two such fragilities are palpable in the interim order as well. To be specific and brief, the Plaintiff, Anil Kapoor maintains, amongst many other things, that some of the multiple defendants in the case have been selling his photographs (autographed or otherwise) without his consent. Brief research into the links/URL no 12 to 19 of infringing third parties mentioned in Annexure A of the interim order reveal that they are links to old-used postcards of the actor now being sold on eBay for a differential price. (See one example pasted below)

The links, 12 to 19 lead to different old images of the actor as printed on physical old-school/vintage postcards. These defendants have been categorised in the suit as John Does.

The Curious Question 1—Could the Doctrine of First Sale be Applicable Here?

A postcard can be taken either as a literary work or an artistic work under sections 2(c) and 2(o) respectively of the Copyright Act, 1957. These vintage picture postcards, if original, are works in which copyright subsists (section 13 of the Copyright Act, 1957). It could vest in the printer/publisher of postcards (name mentioned on the back of the picture in postcards). In such a case, these postcards in the possession of a person ‘X’, who purchased/lawfully acquired these picture postcards in good faith, are just in the nature of books—one can own the product but not the copyright in the content. If this understanding holds, then at least one copyright aspect involved here is the Doctrine of First Sale (sections 14(a)(ii) and 14(c)(iii) of the Copyright Act, 1957). While it is accepted that one cannot commercialise the image of the actor (say by printing it on tee-shirts, cups, key chains, and other merch), because of his image rights being involved, it also holds true per the same doctrine, that even the owner of copyright in the postcard, once it has been sold to ‘X’, cannot control the further movement of the same. Simply put, resale of it, even if at a premium, cannot be stopped. A question arises—can the holder of image rights stop it; legally speaking?

It is notable that the material part of the content in the concerned picture postcards (as revealed by links 12-19, mentioning used postcards), comprise of certain images of the concerned actor. These images are not being ‘reproduced’ by the seller—the latter is simply re-selling the product on eBay. On eBay, sellers list their items for sale or auction. The listings usually mention the item description such as ‘used’ or ‘good condition’ in this case, and also the payment and shipping options.

Given this, it is a bit curious why and how the links appear under the head ‘infringing third parties’.

The Curious Question 2—What About the Doctrine of Laches?

In the bygone era before the advent of social media, picture postcards featuring beloved Indian screen actors were all the rage. Fans, starved for glimpses of their idols. They reveled in collecting and exchanging these postcards, much like stamp enthusiasts with their postage stamps. It would have been virtually impossible for anyone, including the actors themselves, to remain unaware of the widespread existence and popularity of these postcards.

Assuming that the printer/publisher of the concerned postcards printed the same, long long ago, in violation of copyright. Is it just, on the principles of equity, to raise this belated issue now, particularly when there is no specific injury attached? This is a potent question that needs to be decided by the court here.

It is common knowledge that equity favours the awake, not those who snooze and take a break!

For the ‘flagged’ John Does, the suit appears to be barred by the Doctrine of Laches. Such postcards were expected to be routinely in possession of fans at least in bygone times, but the plaintiff, Anil Kapoor failed to take any action since.

In Union of India v. Tarsem Singh (2008) 8 SCC 652para 5, the apex court, albeit in a different context, had the occasion to dwell upon the Doctrine of Laches.

To reproduce [with inputs], ‘One of the exceptions to the said rule [laches]is cases relating to a continuing wrong. Where a claim is based on a continuing wrong, relief can be granted even if there is a long delay in seeking remedy, with reference to the date on which the continuing wrong commenced, if such continuing wrong creates a continuing source of injury. But there is an exception to the exception. If the grievance …affect[s] several others also, and if the reopening of the issue would affect the settled rights of third parties (like the fans who bought those postcards and are aiming to resell now), then the claim will not be entertained.’

Should the above not apply to the claims made by the Plaintiff in the instant case?

Further, in Cable News Network Lp, Lllp (Cnn) v. Cam News Network Limited MIPR 2008 (1) 113, 2008 (36) PTC 255 Del, para 24, the HC of Delhi states that, ‘mere passage of time cannot constitute laches, but if the passage of time can be shown to have lulled defendant into a false sense of security, and the defendant acts in reliance thereon, laches may, in the discretion of the trial court, be found.

When there is a long delay in lodging a protest against an alleged infringement, like in the instant case, harm to the defendant could arise simply because the plaintiff did not act sooner. This delay could have happened because the plaintiff was aware of the infringement or did not think it to be harmful enough to his vocation. Should then the defendant be penalised for being entrapped into a deceptive sense of safety created by the plaintiff’s inaction?

Do these John Doe(s) breach a line?

In my assessment, the answer should be in the negative. Links 12-17 of the alleged third-party infringers merely seem to be innocuous fans hoping to earn extra cash by selling on eBay the used postcards they once cherished. They seem to be protected by the Doctrine of First Sale or the Doctrine of Laches. (In fact, I would love to argue that these fans can even mint an NFT-Non-Fungible Token of the same. After all, it only means listing an NFT on a digital marketplace for sale! —but I would leave that for another post)

Is there any image/ name tarnishment, passing off of/in respect of the actor here? Simply none.

Conclusion

In India, the term ‘personality rights’ gained traction only in the past few years—thanks to litigation involving Gautam Gambhir, and Amitabh Bachchan. Anil Kapoor one being the latest. Celebrities of all kinds are in the business of making money through their persona. Being their bread and butter, it is understandable if aware persons of eminence get fixated to their ‘personality’ or ‘image’ rights.

However, the scenario of courts getting plethoric and lavish in doling out remedies in favour of the celebrity plaintiffs is not comprehensible, for they are Courts of Law. The present interim order does not give sufficient legal reasons for its overarching contents. Something in the same vein has been maintained by the authors in a previous Spicy post in re Amitabh Bachchan HC order.

As the field of law concerning the intersection of copyright and image rights is still in its early stages, with no established legal precedent, it becomes even more imperative that interim orders of this nature evolve beyond being vague and superficial.

Postscript: Should there be Unequivocal Image Rights in India?

Though personality or image rights appear to be an unorthodox form of intellectual property, the answer can be in the affirmative here. One can always learn from Italy who is perhaps the only country whose law firmly assert that using someone’s images, pictures etc. for commercial purposes requires that person’s consent and this is without exception. However, it would be humane, equitable and fair to add that an applicant seeking specific damages for image rights infringement must prove resulting damage, injury, or loss from such infringement. Mentioned John Does do not seem to fit the bill.

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- PlatoHealth. Biotech and Clinical Trials Intelligence. Access Here.

- Source: https://spicyip.com/2023/10/image-rights-alright-but-can-they-trump-established-rights-and-doctrines-should-they.html