LISTEN TO THIS FUEL FOR

THOUGHT PODCAST

The automotive industry is reaching an

inflection point that will reshape its near-term future,

precipitated by the connected car era – also known as software

defined vehicles or “SDVs.” This will affect every aspect of future

mobility, from Generative AI implications in Level 2+ autonomy to

the HMI of the cockpit domain software.

On the eve of CES, automakers and suppliers are

closely monitoring the evolution of connected cars – encapsulated

in the “CASE” acronym of Connected, Autonomous, Shared, and

Electric. This transition will be crucial to rebalancing the

automotive value chain and to how OEMs exert control over the

vehicle assembly process. But this involves more than just the

building of the software-defined vehicle. Automakers also will

attempt to extract more value from the service life of these

vehicles.

OEMs are looking to wrest back control from

tier 1 and system-on-chip (SoC) suppliers involving revenue that

can accrue over a vehicle’s lifetime, including in-vehicle

applications and digitized services that SDVs facilitate with

ease.

The side effect will be a period of upheaval

and rebalancing in the supplier value chain, thus making the

transition complex.

This change threatens to upend the industry’s

value chain, which has been taken for granted since Henry Ford’s

first moving production line in 1913 at Highland Park, and the

accepted orthodoxy of the Toyota Production System that’s shaped

the industry’s value chain through the 20th century and early part

of the 21st.

Of course, such a reshaping of the automotive

value chain will be strewn with obstacles and opposition –

geopolitical and practical – and OEMs will face opposition from

industry participants reluctant to cede their place at the

table.

Historically, the automotive industry has

focused on cost-optimizing hardware, such as with semiconductors.

Software was seen as necessary, but not as strategically important

as hardware. Tesla’s unleashing of the software-defined vehicle –

with its over-the-air updates – challenged the status quo. It’s not

that software wasn’t strategically important, just that the

industry simplified software to the cost of memory.

Development of electronic functions was rooted

in both expediency and cost. The symbiosis between hardware and

software was straightforward: More code simply translated to a more

expensive microcontroller unit (MCU). Minimized hardware costs

minimized software size. This justified the proliferation of MCU

derivatives based on different memory sizes so long as smaller

memory translated into lower hardware cost.

This approach has dominated automotive R&D

thinking for decades, with gentle evolution fitting comfortably

within the existing automotive value chain structures and

traditional platform redesign cadences. OEMs orchestrated material

flows and wielded cost-down power.

Electric

vehicles and the connected car opportunity

OEMs are emboldened by the new E/E

architectures and product development process shifts taking place.

These changes will be evidenced in 2024 and 2025, when Level 2+

automated vehicles, complete with the widespread adoption of

over-the-air (OTA) updates, will become more mainstream.

OTA brings multiple

revenue opportunities. OTA updates also allow the vehicle to be

maintained, updated, and have features added over its lifetime

without visiting a dealership. With OTA, the initial sale of the

vehicle becomes the start, rather than the end, of the

value-extraction process for the automaker.

Within the current industry structure, there is

little incentive in terms of return on investment for automakers to

keep the status quo. The current practice is for hardware suppliers

to embed their software in deliverables. A case in point is

Mobileye’s dominant position in the computer vision space, where

they can leverage both their hardware and software stack. Where the

software is embedded and there is a requirement for post-delivery

customization, there either is a cost implication for the OEM, or

the revenue generated from the innovation is shared with the

vendor.

With the Level 2+ rollout, OEMs are wary of

repeating that experience and being bypassed. With an increasing

set of services being offered over a vehicle’s usage life cycle –

all enabled by software – and knowing that service revenues come

with two- to four times the margins of hardware, OEMs see an

opportunity not to be missed.

Tesla as

harbinger of change

The early success that new-era OEMs like Tesla,

Xpeng, and Nio have had in internalizing software development —

and therefore revenues — has aroused envious glances from

legacy automakers. And they have a point – up to a point. Tesla’s

EBITDA margin continues to outpace its competitors. In 2022, Tesla

recorded a margin of 21.4%, while a selection of 11 of its

established competitors managed an average of 12.6%. Tesla’s margin

in 2022 was nearly 50% more than that of Honda, which was the

strongest-performing competitor, according to S&P Global Market

Intelligence.

Of course, Tesla’s margins are not solely

attributable to its software approach, although it undoubtedly

helps. It eschews advertising, and its platform range is narrow,

which slashes costs. Additionally, other strategies such as the

one-piece gigacasting will

contribute to its bottom line.

But Elon Musk sees the sale of a software

defined vehicle as just the starting point of the consumer

relationship. During Tesla’s Q4 2022 earning call, Musk stated,

“We’re the only ones making cars that, technically, we could sell

for zero profit now and then yield tremendous economies in the

future through autonomy. No one else can do that.”

Musk put that claim to work at the end of 2022,

when Tesla began deep price cuts to its models which lowered its

margins – but still provided a greater return than its peers,

causing jitters in competitors’ electrification strategies.

Tesla’s SDVs also challenge vehicle development

orthodoxy. Rather than a vehicle undergoing costly minor physical

engineering changes every three years, then major architectural and

platform redesigns every six years, the SDV allows for a different

approach via OTA updates. Legacy OEMs will dissent, however,

stating that adopting Tesla’s practices will result in volume decay

for vehicles that suffer long cycles between design changes.

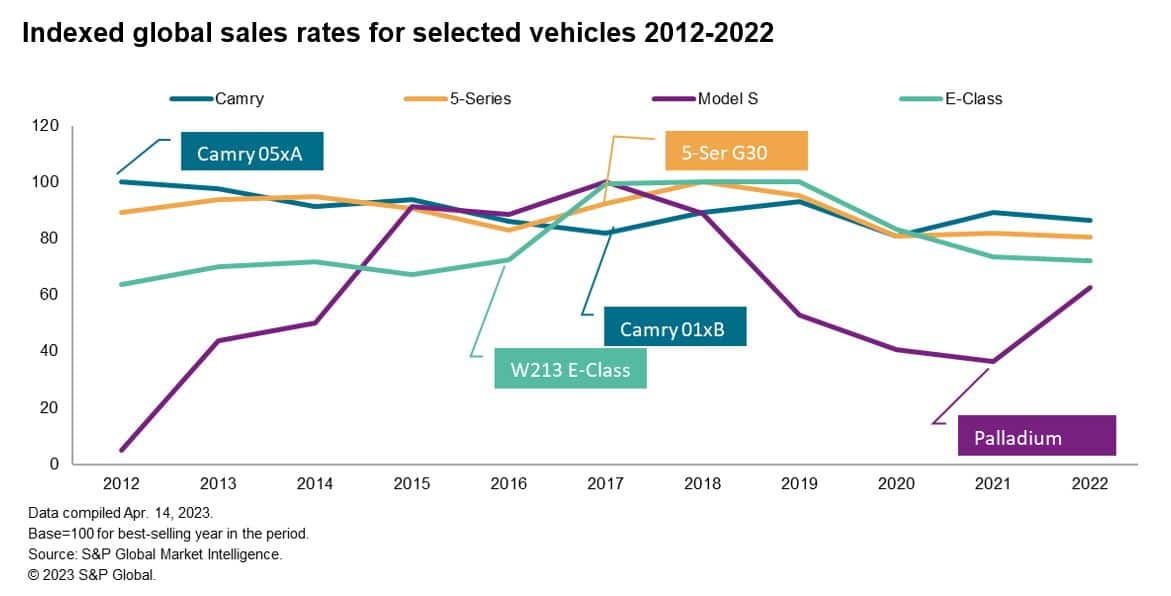

The chart below indexes sales of E-segment

vehicles that compete with the Tesla Model S globally over a period

– beginning with the Model S’s launch year of 2012 through 2022.

Over the 10 years, competing models all underwent significant sheet

metal changes, while the Model S’s 2021 ‘Palladium’ update was far

less involved on a material basis. Whether legacy OEMs will stomach

the prospect of such pronounced sales decay is a moot point.

Middleware and Connected Car development

The battleground for the SDV value chain is

already developing – and the main clash involves middleware.

Foundational components like operating systems

are not an area that OEMs will strategically invest in, but instead

treat like a commodity by signing long-term contracts. The

development of a virtual software layer between hardware and

software by automakers is another area of intense research. This

layer would enable the translation of complex hardware and software

resources into a more straightforward format in the upper layer

software stack.

Achieving this objective allows the separation

of the hardware lifecycle from the software function development.

Each can then function independently, providing more options for

future collaboration with the new software supply chain.

The commodity middleware link will have a

degree of customization and there will be some collaborative

investment, but it will be with one eye on future infrastructure

requirements for SDVs. Currently, this is where companies such as

Mobileye and Nvidia exist.

But automakers want to develop and own the

strategic middleware space. Vendors would have to keep the vendor’s

code or its interfaces, leading to a cost for every customization

and, sometimes, a license fee payable on a per-vehicle basis.

Suppliers rebut this position, insisting that software is not a

core OEM competency – pointing to VW’s notoriously troubled CARIAD

software development. Furthermore, vendors such as Mobileye have

built a formidable power base that will prove challenging for OEMs

to separate responsibilities for software from hardware.

Not all OEMs will have the wherewithal or

desire to own this area of the value chain. Some automakers

actually see a turnkey middleware solution as attractive. This

could be due to the OEMs lacking in-house software capability, not

actively developing SDVs or Level 3 vehicles, or a preference to be

a fast follower rather than a first mover and take advantage of

lower development costs.

The human-machine interface (HMI) and user

experience (UX) is a key part of any OEM’s core competency – and a

brand differentiator in a world of increasingly homogenous vehicle

design. If control of the API and middleware is secured, this will

be an area of 100% OEM participation.

There also is the SDV’s backend to consider.

SDVs need an instantaneous uplink and downlink cloud connection. As

latency is essential in supporting the new business model, it is

likely that OEMs will also seek to own the connection between cloud

platform services and the middleware. This is a path that BMW, VW,

and Tesla have already embarked upon, and others are sure to

follow.

SDVs and

parallel value chains

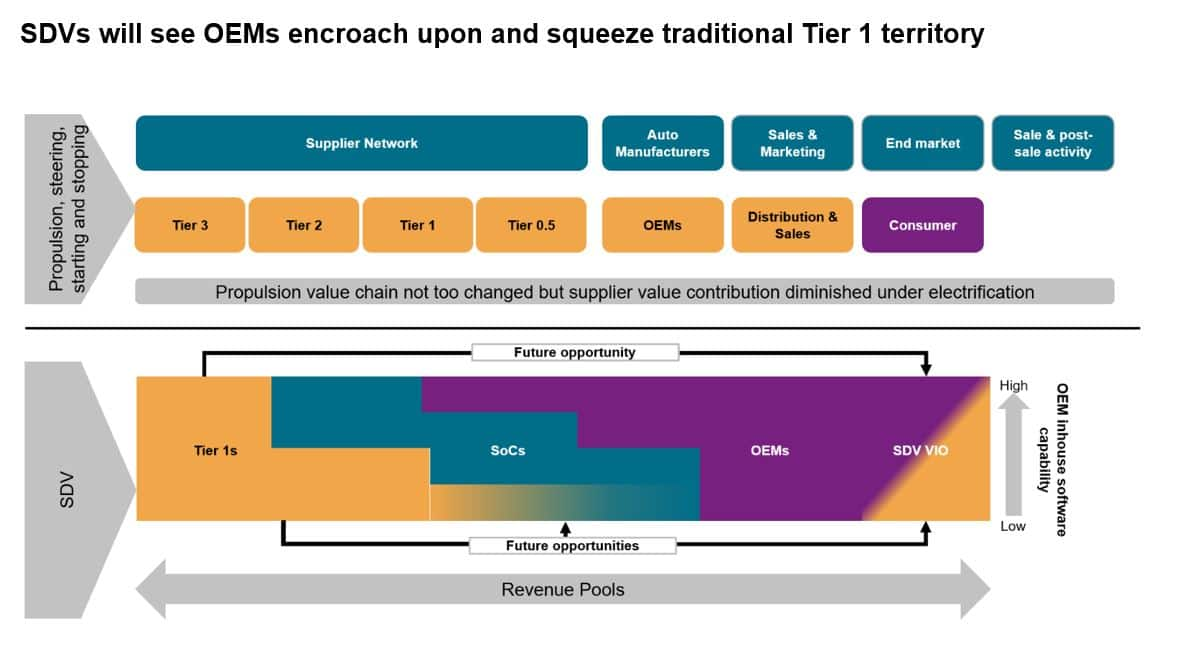

The decoupling of the vehicle development

process from a vehicle’s hardware and software integration under

the SDV megatrend will see two value chains develop in tandem.

While the traditional view of the value chain will last, its focus

will shift to what makes the vehicle move, change direction, and

start and stop.

Electrification will diminish the value that

traditional mechanical components contribute to a bill of materials

(BOM), due to the battery and electric motors becoming bigger

constituent components compared to internal combustion. Because of

the E/E and software revolution, traditional mechanical components

will become increasingly commoditized, placing pressure on the

supply base.

Tier 1 suppliers hoping to use their automotive

software expertise to cash in on SDVs and migrate from their role

as system integrators to software integrators face a battle. In an

idealized scenario, OEMs are reluctant to cede ground to either the

SoC vendors or the tier 1s. However, given the choice of who is

more central to future business, they are likely to choose the SoC

vendors.

OEMs will lead the

decision

Automakers are essential in determining how the

SDV value chain develops. The extent of their involvement will boil

down to the level of in-house software capability. This can be

shaped from a philosophical or strategic viewpoint, or it can be

due to the availability of financial and human resources.

Those without the financial capability to go it

alone will opt for development partnerships in commodity middleware

and foundational parts of the strategic middleware. Here, an OEM

can then use the platform a partner supplies to develop their API.

This allows an OEM to at least have some skin in the game.

For the supplier of the middleware platform

such a partnership also offers a way forward — but relies upon

the supplier having developed a solution set in-house (e.g., Bosch

and ETAS, ZF and Mediator) or acquiring the capability. Such an

arrangement was formed in April 2023 by JLR with Elektrobit, which

is owned by Continental. From 2024, JLR’s EVA Continuum platform

will use Elektrobit’s software platform and operating system.

These new partnerships could portend the end of

eras defined by often confrontational and adversarial supplier

relations. The advent of the SDV could usher in a more

collaborative era, allowing more industry participants to share in

the spoils on offer from the SDV revolution.

————————————————————–

Dive deeper into these mobility insights:

MORE ON THE FUTURE OF MOBILITY AND

CONNECTED CARS

MORE ON AUTONOMY, CAR SHARING AND

ELECTRIFICATION

AUTOMOTIVE PLANNING AND

FORECASTING

TECHNOLOGY VEHICLES IN

OPERATION

This article was published by S&P Global Mobility and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- PlatoHealth. Biotech and Clinical Trials Intelligence. Access Here.

- Source: http://www.spglobal.com/mobility/en/research-analysis/fuel-for-thought-connected-cars-and-the-automotive-revolution.html