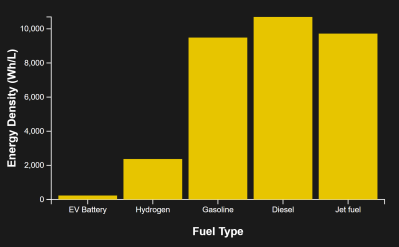

In the automotive world, batteries are quickly becoming the energy source of the future. For heavier-duty tasks, though, they simply don’t cut the mustard. Their energy density, being a small fraction of that of liquid fuels, just can’t get the job done. In areas like these, hydrogen holds some promise as a cleaner fuel of the future.

Universal Hydrogen hopes that hydrogen will do for aviation what batteries can’t. The company has been developing flight-ready fuel cells for this exact purpose, and has begun test flights towards that very goal.

Sky Hydrogen

It’s only recently that battery technology has advanced enough to build decent, usable electric cars. Even still, just getting a few hundred miles of range out of an aerodynamic sedan typically takes over a thousand pounds of batteries. For aircraft, which are significantly more power hungry than cars, batteries simply aren’t a viable power source. Hydrogen, however, could be a viable alternative, as it has an energy density on a par with fossil fuels. It can be burned in internal combustion engines and jet engines, just like fossil fuels, generating no carbon dioxide output and a minimal but measurable amount of nitrogen oxides. Even better, it can be used to produce electrical energy with only water as a byproduct, by using a fuel cell.

Hydrogen is much comparable in energy density to fossil fuels, in both weight and volume. Batteries fare far worse by comparison. Note, however, that this comparison is of the fuel itself, and does not take into account storage infrastructure like the tanks required to maintain hydrogen at the correct temperature and pressure.

For this reason, Universal Hydrogen has been working towards its first major test of fuel cell flight. The company recently completed taxi testing in February, which helped to secure a special airworthiness certificate for its experimental De Havilland Canada Dash 8-300 test aircraft. With that in hand, it was able to pursue the first flight in a planned two-year series of tests.

Traditionally, the Dash 8-300 is a regional turboprop airliner, capable of carrying approximately 50 passengers, depending on configuration. In this case, however, Universal Hydrogen heavily modified the plane, replacing one of its engines with an electric motor from aviation company MagniX. The motor was supplied with electricity from a megawatt-class hydrogen fuel cell, while the plane was also outfitted with two hydrogen tanks carrying a total of 30 kg of fuel.

The modified Dash 8-300 built by Universal Hydrogen.

” data-medium-file=”https://zephyrnet.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/largest-ever-hydrogen-fuel-cell-plane-takes-flight.jpg” data-large-file=”https://zephyrnet.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/largest-ever-hydrogen-fuel-cell-plane-takes-flight-1.jpg?w=800″ decoding=”async” loading=”lazy” class=”size-medium wp-image-582057″ src=”https://zephyrnet.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/largest-ever-hydrogen-fuel-cell-plane-takes-flight.jpg” alt width=”400″ height=”225″ srcset=”https://zephyrnet.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/largest-ever-hydrogen-fuel-cell-plane-takes-flight-1.jpg 3840w, https://zephyrnet.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/largest-ever-hydrogen-fuel-cell-plane-takes-flight-1.jpg?resize=250,141 250w, https://zephyrnet.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/largest-ever-hydrogen-fuel-cell-plane-takes-flight-1.jpg?resize=400,225 400w, https://zephyrnet.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/largest-ever-hydrogen-fuel-cell-plane-takes-flight-1.jpg?resize=800,450 800w, https://zephyrnet.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/largest-ever-hydrogen-fuel-cell-plane-takes-flight-1.jpg?resize=1536,864 1536w, https://zephyrnet.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/largest-ever-hydrogen-fuel-cell-plane-takes-flight-1.jpg?resize=2048,1152 2048w” sizes=”(max-width: 400px) 100vw, 400px”>

For its first live test, the plane, nicknamed Lightning McClean, took to the skies for a fifteen minute flight. It reached an altitude of 3,500 feet above sea level. The fuel cell provided up to 800 kW of electricity during the flight, with water vapor the only output to the atmosphere. Approximately 16 kg of fuel was used in the test.

Of course, aviation is a famously conservative business, hence why the aircraft only ran a single hydrogen-powered motor at this early stage. The Dash 8’s other standard Pratt and Whitney turboprop ran during the flight. However, at one stage, the crew throttled down the turboprop to near-minimum, and the plane flew almost entirely on fuel-cell power alone. For now, the test flights are a low-stakes demo of hydrogen aviation. However, it’s important to collect data in tests like these, in order to get the hydrogen powertrains to the point that they can be certified as flight-ready components.

A Path Forward

While it’s early days yet, Universal Hydrogen has a clear plan for the future of hydrogen in aviation. Its testing doesn’t just serve to demonstrate a hydrogen-powered propulsion system, but also the company’s ideas around how it thinks hydrogen aircraft will be fueled, too.

Universal Hydrogen doesn’t plan for airports to install new hydrogen fuel tanks and refuelling infrastructure. Instead, it employs its own “hydrogen modules” on its aircraft. These standardized modules are essentially large hydrogen cartridges, which the company likens to Nespresso pods. The idea is that they can readily be managed by existing airport freight and logistics infrastructure. The modules can simply be loaded into the fuselage of a plane and hooked up onboard. The way the company sees it, this methodology means every airport around the world is automatically “hydrogen ready.”

Having the fuelling question figured out is key to Universal Hydrogen’s future goals, too. The company already has almost 250 orders from 16 customers on its books to retrofit existing aircraft with its hydrogen powertrain technology. The company expects to begin delivering on these orders, worth over $1 billion, as soon as 2025. That may be a lofty goal given that the company hasn’t yet secured wide-ranging approvals for its technology just yet. However, it’s a major show of faith from established airlines that the company’s order book is already overflowing.

Questions Remain

While the first test flight was a success, there’s still plenty of hurdles for Universal Hydrogen to overcome. The company must secure approvals from the FAA and other relevant authorities around the world for its technology. To achieve this, it must demonstrate that the hardware is up to the fastidious reliability standards expected in the aviation world.

Beyond that, it must also work on the problems surrounding hydrogen storage, transport, and production. The company’s modules are a great idea, but their current solutions will need scaling to tackle anything beyond the shortest flights. Hydrogen may be energy dense when it comes to weight, but by volume, it’s only a quarter as dense as jet fuel. This could impact negatively on payloads for hydrogen-powered planes. Production is an issue too. Running hydrogen through a fuel cell may be clean, but producing the hydrogen can be quite a dirty process in itself. Green hydrogen production methods using clean electricity are key to making it a more sustainable option than digging up more dinosaur juice.

It seems unlikely hydrogen will take off as a mainstream automotive fuel. Despite this, batteries still don’t offer a viable solution for heavy-duty applications like trucks, trains, and planes. Until something better comes along, hydrogen is likely still the best bet to clean up the emissions from these industries. It’s just going to take plenty of grunt work and engineering to make that a reality in the decade or two to come.

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- Platoblockchain. Web3 Metaverse Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- Source: https://hackaday.com/2023/04/03/largest-ever-hydrogen-fuel-cell-plane-takes-flight/