LISTEN TO A PODCAST ON THIS TOPIC

WITH S&P GLOBAL MOBILITY EXPERTS

The projected curve in tractor-trailer

electrification in the US is getting steeper, but a future of

roadways filled with EV and hydrogen big rigs is still strewn with

potholes.

Tougher emissions regulations arriving in 2030,

emerging technological developments, and improvements in the ZEV

medium- and heavy-truck cost picture ‒ with hydrogen in particular

‒ have sharply increased the potential for adoption of ZEV or

near-ZEV commercial vehicles.

In weighing the factors involved in

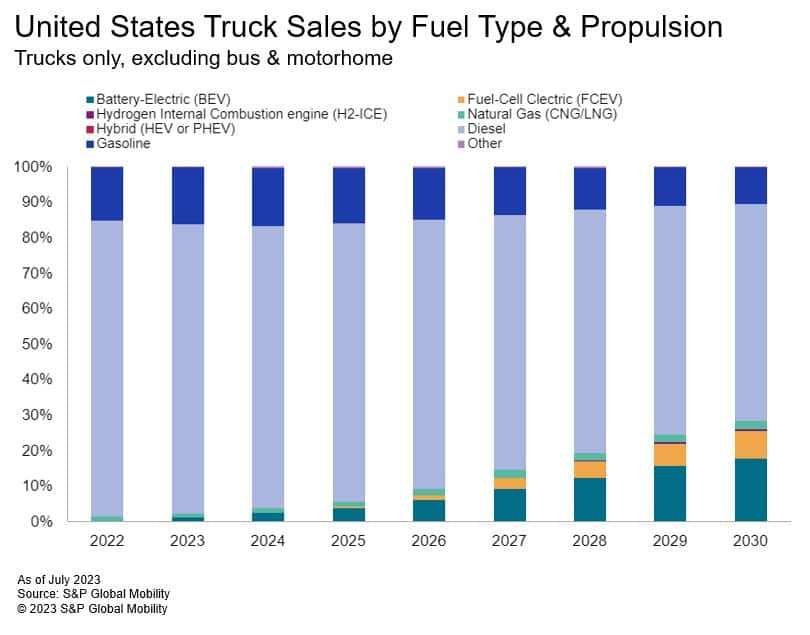

implementing a ZEV big-rig fleet, S&P Global Mobility now

forecasts medium-term ZEV commercial vehicle registrations in the

United States higher than ever before. Expectations for the end of

the decade now reach nearly 140,000 annual new registrations of ZEV

trucks starting in 2030, an expected share of more than 25% of the

Class 4-8 medium- and heavy-duty truck market.

That said, for all the pronouncements of a

future of battery-powered Tesla Semis and hydrogen-fueled Nikolas,

serious impediments remain on the road to mass adoption.

Compared to previous forecasts, S&P Global

Mobility’s most recent projection represents higher volumes in unit

terms, as well as a more rapid expected transition away from

established internal combustion engine (ICE) technologies.

Expressed in terms of the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of

forecast ZEV registrations, the pace of change has risen from 70%

per year to 109% in just two forecast rounds. This steeper expected

adoption curve is due to more than just greater optimism about

prospects for 2030.

Regulatory push

Bullishness for 2030 has grown alongside

increasingly ambitious government regulations and supports ‒

including the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), proposed changes to

Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Phase 2 standards, and proposed GHG Phase 3

standards for MY 2028-2032 from EPA/NHTSA.

The so-called GHG Phase 3 standards reveal a

bold initiative to push the pace of change in the industry ‒

drastically reducing allowable CO2 emissions beyond the 2028

threshold foreseen in Phase 2 ‒ to include reopening and tightening

already-published goals for model year 2027 diesel engines. By MY

2032, the proposed GHG phase 3 regulations will mandate an

incremental OEM fleet average emissions reduction of 37% in the

medium-duty truck (MDT, including Class 2b & 3) and 27% in the

heavy-duty truck (HDT, Class 8) segments, compared to the final

2027 year of GHG Phase 2 standards.

Regulatory bodies are wielding tax credit and

voucher carrots as well as legal sticks to achieve their emissions

targets. For instance, the 30% of value (up to $40,000) incentive

written into the IRA (in the form of a tax credit) for businesses

and tax-exempt organizations that buy a qualified commercial clean

vehicle. In California, proposed incentives for a Class 8 hydrogen

fuel-cell tractor under the Hybrid and Zero Emission Truck and Bus

Voucher Incentive Project (HVIP) could reach as high as $240,000

for a fuel cell electric truck.

These IRA incentives also apply to the cost

side ‒ especially for hydrogen-powered vehicles ‒ in that

incentives can shape the potential cost curve for refueling some

ZEV vehicles. Easing that cost burden would help support the

initial steep capital expense of the two chief hydrogen propulsion

technologies ‒ hydrogen internal combustion (H2 ICE) and hydrogen

fuel cell electric propulsion (FCEV) ‒ in which fuel costs loom

large as a share of cost of ownership.

But most of the technology forcing mandates are

sticks ‒ such as the implementation of Tier 4 emissions for light

commercial vehicles and the Advanced Clean Truck and Advanced Clean

Fleets legislation affecting California and at least six of the

states that follow the California Air Resource Board (CARB)

mandates.

The Advanced Clean Trucks rule requires

manufacturers who sell medium-duty and heavy-duty vehicles (Classes

4-8) to sell an increasing proportion of zero emissions commercial

vehicles from 2024-2035. A partner bill, the Advanced Clean Fleets

rule, is working its way through the rulemaking process. This rule

places requirements on fleets that meet certain characteristics to

also have an increasing percentage of zero emissions commercial

vehicles in their fleets. This rule also goes into effect in 2024.

And by the end of 2023, California also is enacting strict rules

for the types of drayage trucks allowed to idle at intermodal

seaports and railyards.

Getting up to speed

Despite the regulatory push, recent market

performance for ZEV MHCVs has been muted, with new registrations of

ZEV big rigs so far this year below expectations. While US

registration volumes of Class 4-8 ZEVs in the first four months of

2023 had an impressive-sounding 200% year-over-year increase,

supported by the registrations of the first trucks from Nikola and

Tesla, it represented barely 1,100 units and amounted to just 0.6%

of new vehicle registration volume ‒ and was 44% lower than

forecast.

Alongside uncertainty and cost, headwinds have

included the same supply-chain issues that have buffeted the

production of traditional diesel trucks and buses. Among them,

manufacturers have counted lengthy wait times to receive parts;

inability to source sufficient parts; difficulties finding workers

and running full schedules; and elevated input material prices.

In some ways, these problems have been even

more of a challenge for dedicated ZEV startups, which have

typically tighter capital, challenging cash burns, steeper

borrowing rates in the current inflationary cycle, and lower

volumes (and thus revenue) to weather a supply-shortage storm,

compared to larger, relatively more established makers.

In looking at market expectations from just six

months ago, delays in introductions of new Class 4-8 ZEVs have

represented about a quarter of all known or suspected

start-of-production delays for truck and buses overall ‒ well above

the ZEV share of the market.

Dodging potholes

The current high price of hydrogen fuel,

significantly higher than diesel, has been prohibitive for most

would-be hydrogen vehicle buyers. Even in the case of the

theoretically affordable acquisition cost of an H2 ICE truck,

prospective fuel costs have raised questions about the benefits

compared to other propulsion technologies. With the IRA raising the

possibility of hydrogen fuel cost dropping sharply, maybe even to

as low as the diesel gallon equivalent, the opportunities for

hydrogen become brighter, though still not certain. Indeed, more

than two-thirds of the increase in expected 2030 new ZEV truck and

bus volumes comes from anticipated hydrogen truck and bus fuel

price declines.

That said, improved prospects for H2 ICE

depends on H2 ICE products available for purchase. The current

forecast from S&P Global Mobility includes seven H2 ICE truck

models, all expected in Class 8. This is up from just three models

forecast this time a year ago.

Over the next two decades, battery electric

trucks and fuel-cell electric trucks are expected to undergo

significant advancements ‒ paving the way for increased efficiency,

reduced costs, and wider market adoption. It is our expectation

that, with next-generation battery technology, trucks will see

improved energy density and longer-range capabilities, two very

important metrics for truck operations.

Similarly, innovations in hydrogen-related

technologies are anticipated to bring longer range and improved

durability ‒ making them more viable for widespread adoption. As

these technologies continue to mature, economies of scale will

drive down production costs, leading to electric trucks becoming

more competitively priced.

Overall, the main takeaway is that the industry

is at the early stages of innovation of this technology. Improved

capabilities as well as reduced cost will only improve their

competitiveness and popularity of heavy-duty electrified

vehicles.

Demand-side pledges

There are also indirect factors that are

neither the result of carrot nor stick. For example, a number of

companies ‒ some controlling very large fleets of commercial

vehicles ‒ have made aggressive pledges towards the achievement of

carbon neutrality at a corporate level.

For many of these fleets, transportation of

goods is among the largest contributors to their corporate carbon

footprint. For them, the reduction of carbon emissions from the

commercial vehicles they control is one of the most impactful

levers they can pull. PepsiCo has, as a corporation, pledged to be

carbon neutral by 2040 ‒ witness their reported purchase of Tesla

Class 8 Semis. PepsiCo has taken delivery of 54 Tesla Semis to

date, at about $450,000 each.

PepsiCo is not alone. A number of consumer

goods companies have made similar pledges to achieve carbon

neutrality by 2040 or 2050. For many of these companies, reducing

transportation-based carbon emissions offers a quicker and less

capital-intensive approach to reducing carbon footprint when

compared to re-engineering production processes.

Similarly, some of the larger consumer goods

transport companies have also made carbon neutrality pledges with

intent to fulfill their pledges via the aggressive purchase of

ZEVs, some of them also in the “light” commercial vehicle category.

Amazon has plans for a total of 100,000 custom electric

neighborhood delivery vehicles from Rivian by 2030, while FedEx has

committed to carbon-neutrality by 2040, with all parcel pickup and

delivery vehicles being zero emissions by that date.

What needs to be done

In the near-term, regulation, proclamation, and

acquisition are not yet in alignment, and until they are, moving

toward a zero-emission intermodal future faces roadblocks.

In today’s political environment, it seems

likely that regulators will continue to aim ever higher ‒

regardless of real-world economic realities. Over time, this vision

will be supported and re-adjusted by business conditions and cost

realities on the ground ‒ including slower-than-expected early ZEV

commercial vehicle adoption, availability of recharging/refueling

networks, as well as unexpected technology “Eureka!” moments and

subsequent price changes.

But slow adoption now could also mean slower

adoption in the medium term, as large-scale learnings are not

achieved and not shared. Lower numbers early on will also make it

more difficult for disruptor brands in the space to become and

remain financially viable, casting further doubt on a rapid

inflection point early on.

————————————————————–

Dive deeper into these mobility insights:

Commercial Vehicle Forecast: MDHD

truck market coasts through 2024

Supply shortages and new electric

vehicle registrations for US commercial vehicles

Learn more about Medium & Heavy

Commercial Vehicle Industry Forecast

Hydrogen: In it for the long

haul

Can Brazil’s commercial truck fleet

turn electric?

Learn more about Commercial Vehicle

insights and intelligence

This article was published by S&P Global Mobility and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Automotive / EVs, Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- BlockOffsets. Modernizing Environmental Offset Ownership. Access Here.

- Source: http://www.spglobal.com/mobility/en/research-analysis/fuel-for-thought-the-commercial-vehicle-fleet-accelerates.html