[This post has been co-authored with Praharsh Gour. We’re also thankful to Tejaswini Kaushal and Varsha Sharma for their research assistance with this post. Tejaswini is a 3rd-year B.A. LL.B. (Hons.) student at Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University, Lucknow. Varsha is a 5th year law student pursuing B. A. LL.B (Hons.) from Jindal Global Law School, Sonipat.]

Almost two years after the 2021 amendments to the Patent Rules 2003, the Ministry of Commerce and Industry has proposed a fresh set of amendments which, if accepted, can change the Indian Patent landscape substantially. In this post, we will be discussing the proposed amendments which, if passed, can alter the key flexibilities of working statement requirement, pre-grant opposition, information about foreign applications and disclosure of invention claimed divisional application. There are other proposed changes as well like the introduction of an omnibus extension for all the deadlines upon payment of fees (many discussed in Sabeeh’s post here), change in the syllabus for the Patent Agent Exam to include Designs Act and Rules, however, we will not be discussing these for the purpose of this post.

At the risk of a bit of hyperbole, most significantly, the amendments have given up any pretense of caring about why a patent exclusivity is granted in the first place. Indeed, several positive proposed changes are towards streamlining the efficiency of the timeline from application filing to grant – and certainly that’s a much-needed, positive move. However, the point of a patent system is not merely to ensure the grant of patents, but to ensure benefits to society as the main reason for allowing private parties to get this state protection over inventions. This means that patents are to be granted only after the applications clear the well-considered requirements so as to facilitate the patent *bargain* where “patent monopolies” are allowed only for, and to the extent, that proportionate benefits are given to society. Unfortunately, certain other proposed amendments seek to dilute safeguards that had been put in place to ensure that patents are not granted willy-nilly. After the tremendous resistance that India provided during the TRIPS negotiations against strong-arming tactics by various Western nations, it’s a shame to see that India is now capitulating to what essentially aligns with private profit motives in its own internally proposed amendments.

The draft amendment rules were published on August 23 and the Ministry of Commerce and Industry is accepting comments on the draft rules from the public for 30 days as per the notification, i.e., till September 22. It’s not immediately clear whether stakeholder meetings were held before these draft rules were proposed, and if they were, it is anybody’s guess as to who was invited and who wasn’t. Given the short timeline of 30 days, and the difficulty of getting information even through RTIs, let’s bypass that question for now. (though if anyone has information on this, please do share in the comments or via email).

In this post, we’ll look at some of the important proposed amendments and discuss the impact they may have in the future. Long post ahead.

Weakening the Working Requirement

Before discussing the working requirement, it’s essential to recall that historically it has been seen as part of the reasons for granting a patent privilege in the first place. i.e., the focus of the national patent system is on stimulating the national economy and developing industrial activity, and not for the direct purpose of stimulating the patentee’s pursestrings – the latter being allowed purely a proxy for obtaining the former. That is to say, these patent privileges are not meant for merely ensuring no one else can utilise knowledge and for patent holders to maintain their pricing strategies in other countries. This was understood in the very first patent statute of 1623 and also discussed in the Tek Chand and Ayyangar Committee Reports.

Yet, despite having a local working requirement in our laws, it has been consistently ignored by those who were to enforce it, and challenged by those who were to follow it. For a detailed example, see the filings by the respondents in Shamnad Basheer v. UoI and this co-authored report by Prof. Basheer and Rupali Samuel on the working of Bayer’s Nexavar. Even after the 2020 amendment and consequent dilution of the Form 27, the dismal number of filings indicates the general ignorance of the patentees towards this obligation. Of course, patent holders have much to gain if they can sit on patents and not work them – but does the country benefit from this? This is the question that must be focused upon.

What are the Proposals?

The draft rules propose to:

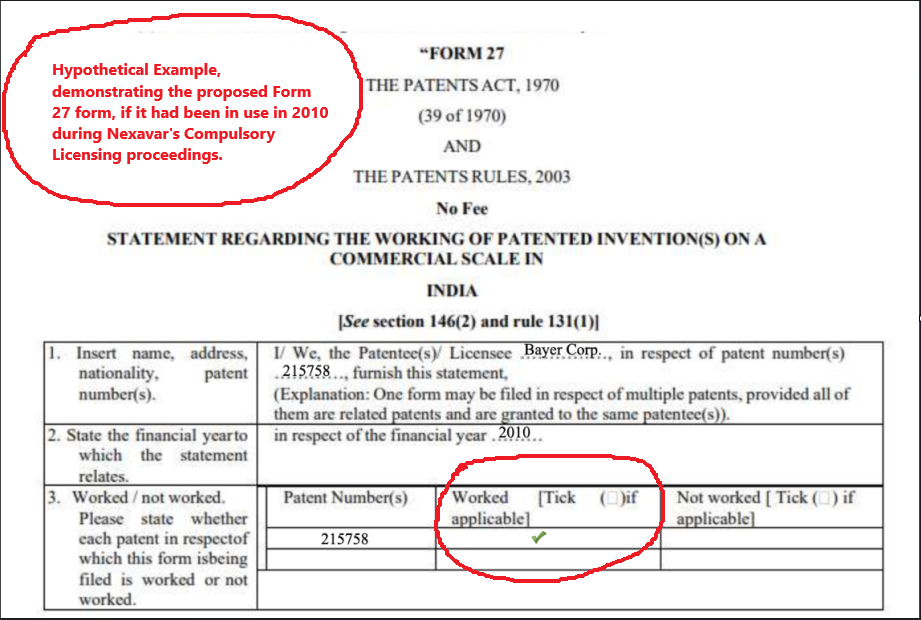

1) Remove the current Form 27 particulars (row 4 and 5) which currently require patent holders to state details of the approximate revenue/ value accrued in India and explain why the patent was not worked (in case it wasn’t).

2) Change the Form 27 filing requirement from every financial year, to once every 3 financial years.

Combined, these essentially removes any realistic response as to whether the patent was actually worked or not. It is important to note here that this information (which would no longer be available) is required for Compulsory Licenses under Section 84(7)(d), as seen clearly in Bayer v. Natco. As a hypothetical example, as can be seen in the picture below, merely having a place holder ‘yes/no’ answer completely defeats the point of the requirement. Without these details, it is essentially diluting the possibility of compulsory licenses as well. For reasons unknown, compulsory licenses have already been reduced to a mere paper flexibility and this change would further ensure that they remain ‘unworked’!

And not just compulsory licenses, but courts have asked for how a patent has been worked for injunction purposes too. For example in Franz Xaver Huemer v. New Yash Engineers the Delhi High Court had categorically stated that if a patent is not worked then an injunction cannot be granted against the respondent. Similarly, in FMC v. GSP Crop Science the Delhi High Court refused to grant an interim injunction over alleged infringement of a patent on Chlorantraniliprol due to non working of the suit patent. Working of a patent was again stressed in an order as recent as 4 August 2023, in Enconcore N.V v. Anjani Technoplast where the Delhi High Court modified the ex-parte interim injunction owing to non working of the patent. Admittedly, there have been differences or further nuances to this approach, for example in EISAI Co Ltd v Satish Reddy, however even if one were to accept this reasoning as generalisable (which would be hard to do), it would still not be an argument to dilute the working requirement.

Apparently filing sparse basic details once in three years may also be too much of a burden for innovative companies, so the rules also propose that the Controller be given the power to condone delays upon payment of some fees. The proposed amendment goes against the scheme of Section 146(2) of the Patent Act which requires such filings to be made every 6 months and presently there is no provision of seeking an extension against this obligation.

Removing Safeguards in Checking Applications

There are two significant proposals that, in the name of easier grant of patents, remove safeguards in the grant/checking process as well.

The first proposed change is towards removing the requirement for applicants to file particulars of every other foreign application of the same invention (within 6 months from filing as in Section 8(1)(b) r/w Rule 12(2)), and replacing it with requiring the applicant to only keep the Controller informed of such foreign filings if objections have been issued against those filings (within 2 months of first statement of objections). [Edit: we had earlier mistakenly written “…. issued against those ‘foreign’ filings” here. Thanks, Roshan John for pointing this out. This has now been corrected].

First of all, it is very likely that the proposed rule is ultra-vires the Act (see Section 8) which clearly states that the requirement is for “every other application”, and not only ‘applications with statements of objections’ issued. So such a proposed rule change would first require a legislative amendment to the Act. Anyhow, let’s look further into the reasoning as well.

Interestingly, this has been described as a method to reduce the burden on patent applicants since this information is already available in the public domain. In essence, the proposal seeks to give more work to the already overburdened patent office, so as to reduce the requirements of those who want the privilege of excluding everyone else in the country from using certain (possible) inventions, by pretending that the patent office would have the wherewithal to check all the patent office databases in the world to keep track of where each applicant might’ve filed, simply because it is ‘in the public domain’. Notably, this interpretation of “Controller can seek and rely on information from available sources/ databases” has already been criticized by the IPAB in Sugen- Cipla Sunitinib patent dispute.

The importance of Section 8 was also emphasized by the IPAB in Fresenius Kabi Oncology Limited v. Glaxo Group Limited where it explained that the purpose of the provision is to ensure disclosure and keep a check on the conduct of the applicant. However, with the proposed amendment the burden shifts significantly on the Controller to “be informed” instead of being “kept informed” and also reduces the scope of information that the Controller should receive, and examines prior to issuing an FER (if at all).

If the intention here is to say that this information that the patent applicant already has, is an unnecessary burden for the patent applicant to produce, then the pretense that its availability in the public domain makes it less of a burden (to a resource-constrained party who has no incentive, versus the patent applicant who is actively seeking the legal privilege of excluding others from utilizing certain inventions), should be dropped.

Making the Pre-grant Oppositions Process Difficult

The draft amendment has the potential to revamp the pre grant opposition proceedings before the Controller. As per current Rule 55, if the Controller, after considering the representation for a pre grant opposition, is of the opinion that application for the patent shall be refused or should be amended, then it can issue a notice to the applicant to that effect. However, as per the draft amendment the Controller has to now assess the “maintainability” of the pre grant opposition and then if it’s of the opinion that the application should be rejected or amended, it will issue the notice to the applicant. Pertinently the rules do not prescribe if the opponent will be given an opportunity to be heard or if the opponent can seek a hearing before the controller with regard to its representation. Further, it does not prescribe if the maintainability of the pre-grant opposition will be judged on the basis of the grounds under Section 25(1) or if there are any other considerations that the Controller will keep in mind.

Apart from assessing maintainability of the pre grant opposition, the rule proposes that once it is found to be maintainable, examination of the subject application should be expedited in accordance with Rule 24C. Though the general sentiment towards timely disposing of applications and oppositions is appreciated, the draft amendment rules nowhere states if the office will be provided with the resources for such expedited examinations. The patent office is already clearly overburdened and adding to this without an appropriate increase in resources and personnel could very easily result in a situation where it is preferable to take the quick and easy method forward, rather than one where time and energy is to be spent on carefully checking opposition claims.

The present rules require fees ranging from INR 4,000 to INR 40,000 for converting an application to an expedited one upon receiving an opposition. However, as per the draft rules, if there is an opposition filed against an application then there is no change in the fees that the applicant would eventually pay for such an expedited examination. Conversely, as discussed below the amendment now imposes a fee on filing a pre grant opposition.

…. And Expensive

Apart from the above changes, the draft rules impose heavy fees on the opponent which not only includes the fees to file an opposition against an application but also to give notice to appear before the Controller for a hearing. Presently, fees are levied only for filing a post grant opposition (INR 2400 for Natural Person and INR 1200 for Others in case of filing an e-copy and INR 2600 for Natural Person and INR 13200 for Others in case of filing a physical copy) whereas, there is no charge for filing a pre grant opposition. But as per the draft amendment rules, now to file a Post and a Pre grant opposition the opponent has to pay an aggregate of actual amount paid by the applicant in applying, filing complete specification, requesting for publication and requesting for examining its application. Apart from the above, another change proposed in the fees schedule is that pre grant opposition can only be filed online and not via a physical copy.

Some very important and basic questions, the answers for which do not appear available anywhere, for those proposing or supporting these changes –

1) How many pre-grant oppositions are filed annually?

2) How many applications are abandoned or rejected after receiving pre-grant oppositions?

[ & 3) Why is this information not available in the Annual Reports already!].

This change in attitude towards the pre grant oppositions somewhat goes against the scheme envisaged in UCB Farchim v. Cipla where the court had held that pre-grant opposition is for the aid of the examiner. With these proposed amendments in place, the opponent now will essentially be paying to assist the Examiner, while the applicant gets the benefit of expedited examination without generally meeting the prescribed qualifications nor even paying up the higher fees for such an examination. In fact, come to think of it, it is unclear how the expedited examination solution as proposed here will be able to overcome the issue of multiple opposition on one hand and repeated claim amendments on the other, as raised by the court in Natco v. Union of India.

One of the reasons for such one sided proposals is perhaps to curb the so called “frivolous” pre grant oppositions (see previous posts here and here) However, (as also argued here), there is yet to be seen any serious evidence as to whether this is a significant problem or a frivolous one. As a thought example – how many patent applications do not result in grants, and is this a reason to increase application fees? Perhaps it is, but surely there would be real evidence based deliberation before such a move was mooted. And imposing hefty fees for filing oppositions without having this deliberation undermines this flexibility substantially. Oppositions are an integral part of the Indian patent regime and serve a key role in assuring that only genuine inventions that meet the prescribed criteria are granted patents (for more detailed discussion on this see here and here).

The amendment also introduces an additional clause (6) to Rule 55, whereby the Controller can decide on accepting/ rejecting the pre-grant opposition and consequently accepting/ rejecting the patent application within three months after the whole exercise of finding the opposition maintainable and the subsequent hearing. However, this is in conflict with the existing Rule 55(5) wherein the Controller has to decide upon the opposition within one month. As argued by Sabeeh here, it is unclear why instead of amending the Rule 55(5), a fresh clause was inserted, which if accepted can lead to confusion.

Broadening the Scope of Divisional Applications

Section 16 of the Act allows such applications where an applicant on their own or because of an objection by the Controller owing to plurality of the inventions, files another patent application for an invention disclosed in provisional or complete specification before the grant of a patent against the earlier filed parent application. The draft rules seek to address a recent controversy regarding this disclosure requirement in the divisional applications.

The timing of this proposal is really interesting as there is an appeal pending on this issue, before the Division Bench of the Delhi High Court. Previously, in Boehringer Ingelheim v. Controller of Patents and Anr. a Single Judge Bench of the Delhi High Court had held that “a divisional application will be maintainable only when the claims of the parent application disclose “plurality of inventions.”” However, a coordinate bench of the High Court in Sygenta Ltd. v. Controller of Patents disagreed with the above understanding and found that for a divisional application to be maintainable, the invention should be disclosed in provisional or complete specification. Consequently, the coordinate bench referred the matter to a Division Bench of the High Court which is up for hearing on the 15th September. The difference between these conflicting understandings as discussed in Sygenta is that provisional specification can be filed without any claims and thus, as per the understanding of Boehringer Ingelheim, no divisional application can be filed where the parent application contains only provisional specification.

On this issue, the draft amendment seeks to expressly clarify that if an applicant desires, it can file a divisional application for an invention disclosed in the provisional specification. This effectively results in a situation where there are multiple applications stemming from a single invention, requiring fresh adjudication. An applicant can file a divisional application with an independent set of claims which will be independent of the claims of the parent application. And thus, if eventually the claims of the parent application are rejected, the claims of the divisional application will still exist regardless of the ground of the above rejection and will require a fresh examination of the claims of the divisional application.

These were merely an indicative list of problems with the proposed amendments and there are a lot more issues with the proposed amendment including the general hike in fees and the provision of omnibus extension which will delay the prosecution proceedings further. The broader issue here seems to stem from the general sentiment of lauding high disposal rates and the eventual grants of the patent by the Indian Patent Office, (see here and here) something which is seen as an achievement of sorts, rather than focusing on the quality of those patents. And these amendments seem like a step further to ensure that grants rather than quality remain the focus.

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Automotive / EVs, Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- PlatoHealth. Biotech and Clinical Trials Intelligence. Access Here.

- ChartPrime. Elevate your Trading Game with ChartPrime. Access Here.

- BlockOffsets. Modernizing Environmental Offset Ownership. Access Here.

- Source: https://spicyip.com/2023/09/draft-patent-amendment-rules-increasing-efficiency-of-granting-patent-monopolies-while-forgetting-the-reason-for-allowing-them-in-the-first-place.html