The US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) on December 8 released guidelines inviting comments on the use of March in rights. SpicyIP intern Jyotpreet Kaur writes on these rights, the changes proposed in the guidelines, and India’s position on similar arrangements. This post has been authored with inputs from Swaraj. Jyotpreet is a third-year law student from the National Law University, Delhi who is interested in Intellectual Property Rights and Competition Law and looks to study their interaction with each other. Her previous posts can be accessed here.

The US’ Review of March-in Rights, and Some Questions on an Indian Counterpart

By Jyotpreet Kaur

As many readers would know, the US government, especially through its US Trade Representative’s office, had been hounding India for years after a single compulsory licence, subjected to much judicial scrutiny, had been granted. It was only during COVID-19 that this pressure stopped being applied so blatantly (with a shift towards ‘trade secrets’ instead). In a very interesting turn of events, it looks like the US is now pushing forward towards guidelines that expand how the US can apply their own version of compulsory licences, a.k.a. “March-in” Rights, domestically! It seems that the domestic pressure resulting from their ever-increasing healthcare costs has reached a point where there is finally some re-examination of how their patent system is affecting costs. On 8th December, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) released draft guidelines inviting comments on the use of “March-In” rights in furtherance of the Biden administration’s objective of lowering drug prices. According to the NIST, the US govt invests approximately $115 billion in R&D through various universities, non-profits, and businesses. March-in rights are provisions that allow the government to require a license for inventions stemming from this investment, upon the fulfilment of certain conditions. Notably, though the ‘threat’ of March-In rights has been brought up before, they have not actually been exercised in the 44 years since the governing Act came into being. The objective of these draft guidelines appears to be the expansion of the criteria under which March-in rights can be exercised. The U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services hailed this as a “powerful tool to ensure that the American taxpayer is getting a fair return on their investment,”

Balancing Innovation and Public Interest: The Bayh-Dole Act’s Objectives vis-a-vis March-in Rights

The Bayh-Dole Act enacted in 1980, brought to the fore amongst other things, the federal government’s “March-in” rights. As mentioned above, March-in rights are akin to inherent measures available to the government in case those developing IPR out of government-funded research have not adequately commercialised the intellectual property. When exercising this power, governments are permitted to intervene and direct the usage of the IPR or licence it to a third party. The ownership of the patent remains with the institute – it is only a right to licence to third parties which is accrued in favour of the government if it chooses to exercise this right. The purpose of this right is to enable the government to fully realise the potential of the public-funded IPR in question if it is being underutilised by the inventor institute.

The exercise of March-in rights under the Bayh-Dole Act is envisaged under 35 U.S.C. § 203, which requires 4 statutory criteria to be fulfilled. These are (i) failing to effectively realise the subject innovation; (ii) the need to alleviate unaddressed health or safety needs; (iii) failure to meet the requirements of public use of the invention; and (iv) failure of contractual obligations, especially under s. 204., which requires patented products to be significantly manufactured in the US until it is commercially infeasible.

To date, march-in rights have not been exercised by the US Government despite petitions seeking the same. The first time a petition was filed for the exercise of March-in rights was in re CellPro where the Government refused to exercise this right. This trend has been continuing to date as can be seen from the eight petitions which have been filed before the NIH and been disposed of.

Revamping March-in Rights: A Recipe for Disaster or Formula of Success?

One of the changes introduced through the guidelines has been to clarify the informal agency consultation process with the contractor prior to the exercise of march-in rights, and increase the allowable time frame an agency has to respond to the contractor following the informal consultation from 60 days to 120 days.

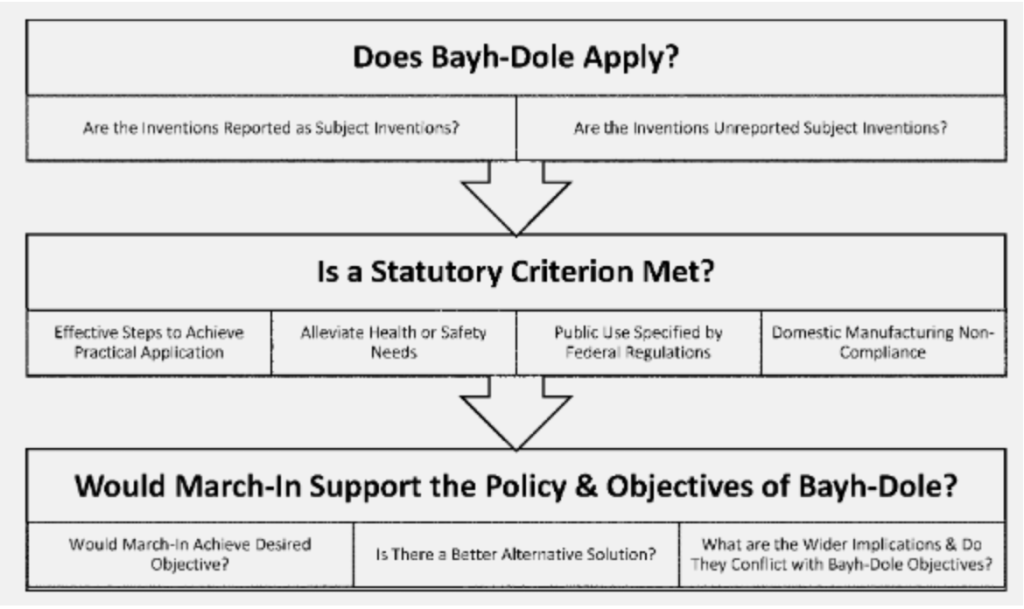

Apart from this, the new guidelines introduce a three-step method which seems to clarify the process to invoke the march-in rights (see image). Firstly, it is to be seen if the Bayh-Dole Act applies to the inventions in question – herein, it is checked if the said inventions are “subject-inventions” and if they are government-funded. Secondly, whether any of the four statutory criteria, as mentioned above, are applicable to the case at hand, and finally, whether the exercise of march-in rights is in pursuance to the overall spirit of the Bayh-Dole legislation and its objectives.

Perhaps the most important change is seen in the second step while invoking the 1st statutory criteria, i.e., when the patent grantee has failed to or will fail to take effective steps for the realisation of the “subject innovation” in its field of use. The guidelines have added a consideration of factors that may “unreasonably limit the availability of the invention to the public.” Here, the guidelines have introduced a requirement of reasonable pricing which was earlier not recognized as a criterion for the exercise of “March-in” rights. The guidelines entail asking the question of whether “the contractor or licensee made the product available only to a narrow set of consumers or customers because of high pricing”.

This is in contrast to the earlier stance of the government which can be evidenced from its previous interactions with high pricing as a ground to exercise march-in. In 2004, the petitioner moved the NIH to invoke this measure because of the high price of an HIV treatment drug called Norvir and a glaucoma treatment drug titled Xalatan. In 2012, the concern surrounding the high price of Norvir was raised again before the NIH. Again, in 2016, petitioners raised concerns surrounding the high price of the Xtandi drug which cost around $98 per pill as compared to other high-income countries. However, in all these cases, the NIH refused to exercise its march-in rights simply on the grounds of pricing citing other reasons for refusing to do so.

Where the guidelines speak about reasonable pricing, they fail to address what a ‘reasonable’ price may be, leaving this to the discretion of the federal government.

Proponents hail these guidelines as progressive measures to make exorbitant drugs more accessible to the general American public and to give back to the public what is “rightfully” theirs since federally funded research is essentially covered using taxpayers’ money.

On the other hand, those who oppose the guidelines argue that these are antithetical to the objectives of the Bayh-Dole Act since pricing was never envisaged as a ground for exercising “March-in” rights. The US Chamber of Commerce has called these guidelines a form of “government confiscation”. Others argue that such a clause would inhibit innovation and competition – which are the primary objectives of the Act. Some have argued that the goal of the Act was to encourage collaboration between the public and private sectors for the purpose of introducing novel ideas into the market unlike what the present guidelines seek to achieve – the alleviation of drug access issues and market inefficiencies. Joseph Allen has also argued that these guidelines are a ‘poison pill’ as although it is aimed at targeting ‘big pharma’, it will end up harming the small inventors who are actually covered under the Bayh-Dole Act because most of the ‘Big-Pharma’s’ research is not government funded. At the same time, he argues that these guidelines have been framed keeping in mind (only) high drug prices, and ignoring that the Bayh-Dole also covers other industries such as energy, agriculture, and environment protection which will now be impacted by the adversities of these guidelines.

What’s Happening on the Indian Front?

Now that this debate is being taken more seriously in the US, will this have any spillover effects in India? While India’s on-paper patent flexibilities are quite robust, and some, like Section 3(d) have made their presence felt, we have yet to see the translation or practice of many other provisions into real-world effects. For example, though there have been discussions of compulsory licences for a couple of other drugs, nothing has come out of these discussions. It’s unclear how much of this is due to external pressure, for example, various FTAs and of course the USTR; and how much of this is possibly due to other reasons. For instance, although India was among those at the forefront while asking for IP Waivers during the Covid-19 pandemic, ironically, at the domestic level, though the Government had a number of options it could’ve taken, not much action was taken. For example, the Government failed to provide clarity over the ownership of IPR (Covaxin) and its act of “granting approval” to Haffkine Institute was something which should have been undermined by the public interest in the “right to health” as has been argued here and here. Similarly, the Indian Government had refused to disclose the Clinical Trial Data through RTI citing Section 8(1)(d) and (e) which provide IPR as a ground for exempting disclosure. The state has invoked the protection of IPRs in rejecting the publication of data without engaging in the balancing act of weighing this protection against the public interest at stake (which has also been provided in S. 39(3) of the TRIPS). Thus, the state has failed to exercise its own IP in an open manner in contrast to its international stance.

Regardless, the US’ internal discussion about something that they have taken strong international positions against to date, is an interesting development to follow. At home, the Department of Bio-Technology recently released its own set of IP guidelines for inventions arising out of DBT funding. How does this fare and does this mark the beginning of another attempt to resuscitate the failed “Protection and Utilisation of Public Funded IP Bill”? At the same time, the Government came out with the National Policy on Research and Development and Innovation in Pharma-MedTech Sector (see the draft policy here) in September 2023 to “transform” India’s Pharma sector and “catalyse” R&D in these sectors in a two-fold manner – strengthening research infrastructure and promoting research in the pharmaceutical sector. Notably, this policy does not address questions surrounding IP at all. Perhaps these are all some questions that are worth pondering upon and ones that we’ll try to put together a separate post on!

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- PlatoHealth. Biotech and Clinical Trials Intelligence. Access Here.

- Source: https://spicyip.com/2024/01/the-us-review-of-march-in-rights-and-some-questions-on-an-indian-counterpart.html