Since 2021, China’s “Whole County PV” programme has been dramatically expanding the use of solar power in rural areas, by building on government, commercial, industrial and residential rooftops.

However, the programme faces a number of obstacles, with problems reported, for example, in the rollout in the province of Shandong in eastern China.

Yet it also offers advantages that can overcome the problem of scale. Installing solar photovoltaic (PV) panels on rooftops over a large area can clear out administrative burdens and reduce “soft costs”, which are inherent in marketing and installing solar to households or businesses one by one.

This raises an intriguing possibility: could such a programme work for other clean energy improvements, such as energy efficiency or clean heating?

Based on my new analysis for the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies of the Chinese counties participating in the Whole County PV programme, the answer appears to be yes.

Moreover, I found that the solar programme would pair surprisingly well with electric heat pumps.

This is an important finding, given the huge scale of rural China, which is home to hundreds of millions of people and is larger than many world regions. And it could also help to address another challenge: China’s rural residents currently suffer a high burden of health issues due to the use of coal for heat and power.

What is China’s Whole County PV programme?

Up until recently, most solar PV in China was installed in remote western regions, requiring costly transmission lines to bring the electricity to eastern provinces that use the most power.

A series of huge “clean energy bases” in desert regions continue to be an important part of the country’s energy transition. Yet these large-scale, centralised developments have provided little low-carbon electricity to hundreds of millions of residents in rural areas.

The Whole County PV pilot programme, initiated by China’s top energy regulator, the National Energy Administration (NEA), in June 2021, has been developed to expand the use of distributed rooftop solar, including in rural communities.

By September 2021, the NEA had published a list of 676 participating counties and other administrative units – representing roughly half of China’s county-level areas.

The counties participating in the programme are not all rural, but they have a lower degree of urbanisation than average, reflecting the goals of the programme.

Despite accounting for around half the county-level areas, they represent just 24% of the country’s population – a nevertheless sizeable number of people.

The programme calls for participating counties to add solar PV to 20% of residential rooftops, along with other targets for commercial, industrial and government rooftops.

The primary innovation contained in the programme is to enable counties to conduct a single auction to cover all the rooftops, which can substantially reduce the soft costs.

The Whole County PV programme is also not limited to sparsely populated areas of western China where large PV projects are usually located.

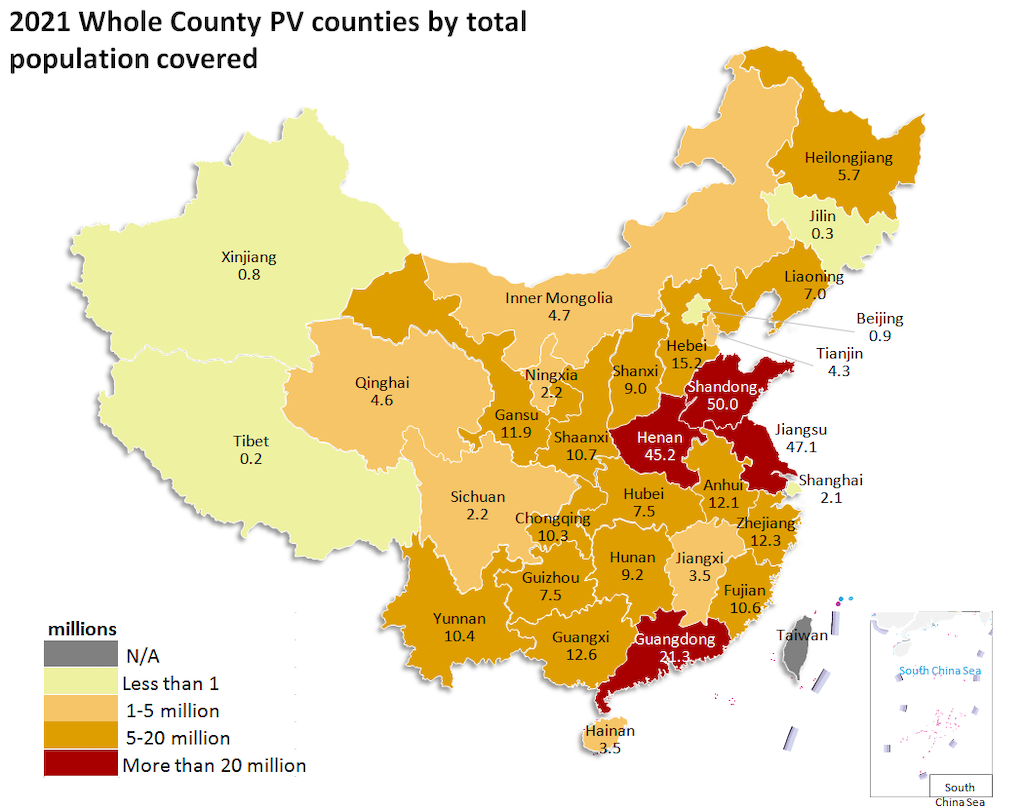

As shown in the map below, the provinces of Guangdong (south), Henan (central), Shandong (central east) and Jiangsu (southeast), marked dark red, have the highest share of county population covered by the programme.

Except Guangdong, the other three provinces have seen roughly half their counties sign up, with a combined population of more than 140 million people.

In general, there are fewer people, marked light yellow, in counties participating in the programme in the west than in the east, marked amber.

The primary innovation of the programme is reducing the costs of distributed solar – especially the soft costs of customer acquisition and contracting – via a tender or auction to select a single supplier and installer to cover all the rooftop installations included in each county pilot.

The programme has already been credited with a dramatic increase in distributed solar since its launch. The National Development and the Reform Commission (NDRC), the planning body of the Chinese central government, has noted the programme had more than 66 gigawatts (GW) of planned projects being registered by the end of 2022.

(For context, this is roughly equivalent to the entire solar capacity of Germany, which has the world’s fourth-largest total.)

However, it has not been without challenges, with Shandong and Hebei provinces facing criticism for flouting NEA directives by temporarily suspending all new rooftop installations or giving preferential treatment to state-owned enterprises. Even so, Shandong anticipates the programme could add 20GW to the province’s total solar capacity by the end of 2025.

A more general challenge is integrating solar in rural areas, where excess peak PV output in midday could overwhelm local grids.

Shandong and other provinces have imposed storage requirements on distributed solar to address this issue, but our research finds that this raises costs and could jeopardise the economics of solar.

Could the Whole County PV programme be expanded to heat pumps?

Heat pumps and solar PV are typically treated as two separate fields: PV is energy production and heat pumps are building energy efficiency.

Policymakers treat them as different topics, assign them to different ministries, offer different incentives and set separate targets.

Today, however, it is worth thinking about how to combine low-carbon technologies, as part of China’s policies calling for integration of electricity supply, grid and demand.

Under the right conditions, heat pumps can help increase consumption of locally produced solar power. The use of solar powered heat pumps can also negate the need for existing heating systems that use fossil fuels, associated with greenhouse gas emissions and negative impacts on local and indoor air quality.

If a house already has solar, using the cheap electricity it produces to power a heat pump improves the economics of the combined system, my analysis found.

Though electricity in China is relatively inexpensive, heat pumps still offer a better payback for households or villages that can generate their own electricity, compared to feeding excess PV power back into the grid at midday.

This not only works in the heat of summer, when heat pumps can be used for cooling. We found that combining PV with heat pumps also offers economic benefits in winter, even though the need for heating may not overlap with daylight hours when solar is generating electricity.

China experiences much sunnier winters than most other countries. In Shandong, for example, a household solar panel might produce 76% as much electricity over the whole winter compared to summer – comparable to Phoenix, Arizona. Contrast that with London or Munich, where wintertime PV output will average only 20-25% of summer levels.

Adding heat pumps can also increase the amount of PV-generated electricity that the household can use itself, rather than exporting back to the grid – referred to as “self-consumption”. Heat pumps push this metric from well below 10% without heat pumps up to 20%-30%, depending on the climate zone. With storage added, self-consumption can reach more than 40%.

Most importantly, we found that adding heat pumps to existing solar households is economically compelling, despite their high initial capital costs.

In most of central and eastern China, we found that the higher upfront cost of adding heat pumps to existing PV households, relative to a new resistance heating or gas boiler, would typically be paid back within six years, shown by the darker colour shading in the three maps below.

What are the barriers to rural heat pump use?

In recent decades, China has given increased attention and investment to the energy transition in rural areas, both to improve the quality of life through reducing indoor air emissions, and to benefit rural households economically by promoting low-carbon energy.

But rural areas face specific barriers, especially when it comes to adopting heat pumps.

In our report, we identified three major issues, all of which could potentially be addressed via the Whole County PV programme, or a similar scheme.

The first barrier is public awareness. In urban China, the building of heating systems is largely a matter for building owners and local heating enterprises, while rural residents tend to view building energy efficiency and low-emissions heating as a government responsibility.

Moreover, in rural China, we found that there is little awareness of the potential cost savings from adopting “clean heating”, which in China includes “clean coal” stoves and gas.

Capital costs are a second barrier, given near universal consumer resistance to spending more upfront on efficient devices that save money over time.

The Whole County PV programme could help alleviate this concern by pooling programme capital costs with commercial and industrial customers, which may be better able to finance such investments through energy services companies or commercial loans.

Administrative capacity and coordination represents a third barrier. Historically, energy efficiency and low-emission energy policies in rural areas have suffered from unclear responsibilities, fragmentation among different government bodies and poor enforcement.

The design of the Whole County PV programme could at least help resolve some of these coordination issues.

What does the future hold for the programme?

Our research shows that there is significant potential to build on the success of the Whole County PV programme.

With a combined population well over 100 million, the participating counties could contribute a significant amount of solar generation in the coming years, even if many counties fall short of the initial targets.

In addition, our analysis suggests that the Whole County PV programme could be a model for policies in China and elsewhere, addressing the soft cost problem while helping small rural residents who otherwise see little reason to invest time and energy – let alone money – in changing how they power, heat, or cool their homes.

A move now to scale up heat pump adoption in China could further reduce emissions in its own right, as well as scaling up the installation of low-cost heat pumps in other parts of the developing world, where cooling demand is likely to grow incredibly rapidly in coming years as the planet warms.

While a major benefit we identified from pairing PV with heat pumps is lower heating emissions, PV paired with cooling could also help absorb the solar and the summertime peak electricity load.

Our research shows how the innovative policy design of the Whole County PV programme could be expanded into other technologies, bringing wider benefits in terms of economics, greenhouse gas emissions, air pollution and the integration of additional solar energy.

Sharelines from this story

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- EVM Finance. Unified Interface for Decentralized Finance. Access Here.

- Quantum Media Group. IR/PR Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Data Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- Source: https://www.carbonbrief.org/guest-post-how-chinas-rural-solar-policy-could-also-boost-heat-pumps/