Every year, a diverse community of over 40,000 music creators in India produces a remarkable 20,000 to 25,000 original songs! This sector contributes substantially to India’s revenue, accounting for over INR 12,000 crore, translating to approximately 6% of the entire Media and Entertainment industry. The country’s music publishing industry has grown significantly, reaching INR 845 crore during FY 2022-23. These are some highlights from the recently released report from E&Y titled ‘The Rise of Music Publishing in India’ based on figures by the Indian Performing Right Society (IPRS) (the copyright society concerned with music publishing). As explained by Ashish Pherwani, Partner, Media and Entertainment, E&Y India, the report aims to capture the state of music publishing in India, its market potential, and (perhaps the first of its kind in India) results of the survey of 500 music creators. The E&Y report is rather an interesting read and most definitely a needed initiative in light of the growing music industry in India, especially in light of the booming streaming business in the country. However, the report is notable for the discussion on the ‘unorganized sector’ (as the report classifies it), which hasn’t received sufficient recognition in previously released annual reports by IFPI, IMI, PwC, Deloitte, KPMG, etc. This post will delve into the discussions surrounding the IPR compliances and implications outlined in the report.

A Call for an Improved Social Security Net

The most interesting part of the report is Chapter 5, which analyses the existing social security net available to musicians. In contrast to some countries providing pension plans for creators over 60, many in India lack provident funds and social security. The report points out that one-time, on-call opportunities like session works, concerts, performance gigs, etc. are the primary sources of employment for these artists, making royalties their primary source of income. Though not directly tied in, the gig nature of employment would presumably result in popular artists and composers being employed more often than the relatively lesser-known ones.

This starkly resonates with the realities about the economic state of artists as pointed out by Javed Akhtar in his (now a decade-old!) speech in the Parliament while introducing the Copyright (Amendment) Bill 2012. Though the report points out that there are certain government schemes for artists and promotion of art and culture like the Artistes Pension Scheme and Welfare Fund, the report calls for more attention to the need for financial assistance to music creators, the need of which was made evident during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Government Policy Perspective

The gig employment (on-call) nature of the music industry prompts the report to point out the implementation of special schemes in some countries, such as the French Social Security Code Article L.382-1, the 1983 German scheme for artists, and Latin American labor codes. These initiatives, coupled with temporary incentive systems by several other countries across the globe, came in handy to incentivize gig workers who were rendered unemployed during the COVID-19 pandemic in their respective countries.

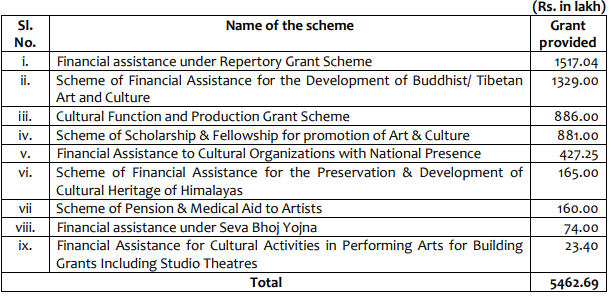

Comparing this with the initiatives of the Indian government, the initiatives are rather middle-of-the-road. The pecuniary help provided seems to be on-point from the government’s standpoint. For assistance, the funds released under the different schemes during the COVID-19 pandemic are as follows:

A grant of a whopping INR 54.62 crores is what the Ministry of Culture and Tourism seems to have given out in its bid to support artists during Covid-19!

While the initiatives are all there, effective implementation remains amiss. Although grants seem to have been released, the information regarding effective compliance for reaching their target audience was missing. Individual and personal efforts, including facilitating international work tie-ups, were rather forthcoming during the COVID-19 period for artists in distress than government initiatives and help, as reflected in this article by The Wire.

Apart from the above measures taken during the pandemic, the Ministry has other schemes providing financial assistance to the artists. For instance, the ‘Financial Assistance for Veteran Artists’, is meant for elderly artists and scholars facing financial hardship so as to improve their socio-economic conditions. But how and how much of these funds were actually used? As evident from the data released by the Rajya Sabha in December 2022, there seems to be a gap in terms of the amount allotted in the scheme and the amount actually used.

| Financial Year | Fund Allocated BE/RE (Rs. in crore) | Fund released/spent (Rs. in crore) |

| 2019-2020 | 21.15 | 18.17 |

| 2020-2021 | 12.36 | 8.71 |

| 2021-2022 | 17.27 | 15.42 |

| 2022-2023 (till 08.12.2022) | 19.90 | 4.29 |

This reflects a good INR 2.98, 4.19, and 1.85 crores differences in the fund allocation and actual spending for artist welfare! This is concerning given how many of these artists are not able to get the funds that are meant for them.

IPRS’s Revenues versus Contributions: A Disparity?

Leaving aside the steps by the government, registration with IPRS in India should benefit artists since the organization enables the collection of royalties through licensing, and ensures fair distribution of collected royalties among authors, composers, and publishers, thus providing a crucial avenue for financial support and recognition in the industry.

IPRS is clearly on an upward trend as a representative organization, with its revenues burgeoning over the years (previously covered here). IPRS revenue increased by 79.7% year on year, rising from INR 313.8 Crores to INR 564 crores! While IPRS has expanded its revenue, supported by the Government of India’s efforts to protect IPRs of the music industry (highlighted in a ToI coverage here), much remains to be achieved for those it represents.

Despite claims of distributing over INR 393 crores during COVID-19, the report highlights the stark contrast with foreign nations, where India noticeably lags in providing adequate social security measures for its musicians. Though IPRS did contribute during COVID, it had also made a lot of money, and the report does not specify the amount actually disbursed as royalties to the members of IPRS.

Royalties for Grabs, no Takers?

A real head-scratcher that emerges from the report’s findings is music creators’ low uptake of royalties. A work enjoys protection throughout the lifetime of musicians and composers and then for sixty years posthumously. And as evident from the state of affairs discussed above, royalties here are not just a paycheck, but also a retirement plan for the creators and a legacy for their heirs. However, it looks like not everyone has jumped on the gravy boat as only around 13,500 of an estimated 60,000 music creators have registered themselves with IPRS.

Highlighting the Problems

The overarching problems within the music industry that are highlighted within the report can be classified as, firstly, artists not registering themselves, and secondly, IPRS not being able to get proper royalties.

For the first, one angle is the lack of sufficient clarity among the concerned artists regarding ownership of their rights. Industry groups highlight that many creators are unaware of their rights and that monetization is contingent upon registering their work with the Society. The report highlights that although publishers can register on behalf of authors with the IPRS, payments are only possible if authors are also individually registered. This leads to another problem i.e. the complicated process of registration within IPRS. This is an interesting bit, especially in light of Anupam Roy’s comment in the report (page 37), that artists often neglect registering their work due to the cumbersome process of individually registering each composition. He also recommended that an automated registration system, like a confirmation email with a one-click registration option, could encourage more authors to register their work efficiently.

For the second part, the issues and statistics raised about compliance in the report are noteworthy:

- Debate Over Payment of Publishing Rights

The report states that there is uncertainty regarding whether publishing rights need to be paid, particularly in the context of radio broadcasters, and notes that this issue has been under judical scrutiny for a decade. However,the citation for this assertion simply says “internal data” which is clearly problematic since it restricts verifiable transparency to ascertain the source’s veracity and objectivity.

- Unclear Justification for Separate Publishing Royalties

A significant point of contention arises from the lack of consensus on why separate royalties for publishing rights are necessary. Some entities, including 796 TV channels, 1,033 radio stations, and major digital service providers in India, question the need for distinct payments, citing either legal ambiguity or the belief that their existing payments for sound recordings cover publishing rights.

- Insufficient Infrastructure for Royalty Determination

The music publishing industry faces a substantial challenge in obtaining, cleaning, processing, and determining royalties. This complex process requires multiple technological interventions, hindering efficient royalty management. However, this challenge also presents an opportunity for India, known for its high-quality back office services, to develop and operate global licensing and royalty distribution systems.

- Non-Participation of Music Companies in IPRS

Despite the importance of the IPRS in collecting royalties, two major music companies that own publishing rights are not members of IPRS. Furthermore, some organizations argue that IPRS only collects the authors’ share of royalties, adding another layer of complexity to the landscape.

Thoughts and Reflections

This report is vaguely reminiscent of the 2017 report by BCG on music in New York City. In my reading, it adequately contributes to the practical understanding of current trends, economics, and opportunities within the music industry in India, especially in the social security domain.

What about areas that could use some further light / improvement? While the report intends to be and is, to a significant level, highly comprehensive and more inclusive, the categorization of the “unorganized sector” is still ambiguous. While some statistical references in the report are inclusive of the unorganized sector, some are devoid of it. This hampers the assertions owing to the volatility of which subsets of the population are being included or excluded when different data is being derived. For instance, while the unorganized is inclusive at most statistical assertions across the report, the page 7 statistic: “Each year, 20,000 to 25,000 original songs are made by over 40,000 music creators in India” explicitly excludes it. Similarly, on page 9: “10 million+ Live events and weddings, most of which consume music.” excludes the unorganized sector yet again. Opinions of musicians belonging to collection societies have found a place in the report even though they are from the unorganized sector, but those lacking any such associations remain under the shroud of obscurity. This in itself spotlights the near impossibility of achieving comprehensive coverage in our diverse country, where a majority of professional and commercially active musicians remain shrouded in obscurity.

Regardless, it is an interesting report for its initiative and in-depthness and is likely to bring much more and about our country into public discussion. There lies a pressing need to elevate music education capabilities in India, given the current disorganization and lack of standardization in this field, and his report makes its fair share of efforts to put the urgency across to the stakeholders.

(Thanks to Achille Forler, who contributed to this report, for directing us to it and highlighting chapter 5 in particular.)

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- PlatoHealth. Biotech and Clinical Trials Intelligence. Access Here.

- Source: https://spicyip.com/2024/02/ey-report-on-the-rise-of-music-publishing-india-reflections-from-an-ipr-perspective.html