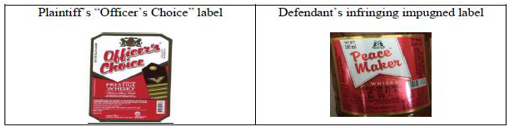

Do you enjoy your whiskey? Would you mix up these two labels: Officers choice and Peace Maker? (image below). Well, it appears the courts think most consumers would. Finding these competing labels to be similar, the Delhi High Court (DHC) recently gave Allied Blenders an interim injunction against Hermes Distilleries following claims of trademark infringement of their label in Allied Blenders & Distillers (P) Ltd. v. Hermes Distillery (P) Ltd., This post assesses the propriety of the judicial examination of the grounds for an injunction order by the DHC.

A bit of factual background before we move ahead to the legal analysis:

Allied Blenders, a liquor manufacturer, has held a registered trademark for ‘OFFICER’S CHOICE PRESTIGE WHISKY’ label since 2013. It alleged infringement by the Hermes Distillery’s use of an allegedly similar ‘PEACE MAKER PRESTIGE WHISKY’ label, which the latter introduced in 2019. Allied Blenders alleged that the Hermes’ label shared significant similarities with its “Officer’s Choice” label, including the positioning of brand names, font style and color, product description, placement of marks, color scheme, border design, and central design element. The plaintiff initiated the current legal action under Sections 134 (forum for filing a suit for infringement) and 135 (relief in suits for infringement or for passing off) of the Trade Marks Act, 1999 to secure an injunction against the defendant’s use of the contested mark.

In response, Hermes argued the case on two grounds:

- That the “Officer’s Choice” marks have been inconsistent over time, and the red and white color combinations were common to their trade.

- That the court lacked jurisdiction as the defendant (based in Karnataka) hadn’t sold the disputed ‘PEACE MAKER’ product in Delhi. They further argued that they lack a distribution license for it in Delhi, and neither party has a registered office or conducts their business in Delhi.

Whiskey Wisdom: Analysing the DHC Order

The Delhi High Court issued an interim injunction order against the Karnataka-based manufacturer, prohibiting them from selling whiskey and other liquor products under the label “Peace Maker.” However, the injunction allows the defendant to use the red and white color combination, provided that it does not cause confusion, deception, or imitation of the plaintiff’s mark/label ‘OFFICERS CHOICE.’.

The Court rejected the defendant’s arguments:

- Did the defendant’s label violate the plaintiff’s rights, constituting infringement or passing off?

The Court noted similarities between the labels, including the use of a ribbon-like feature, the placement of a white window on a red background, the inclusion of an insignia/coat of arms, and the arrangement of other descriptive elements, despite not being identical. The court employed the test of similarity here, assessing the labels from the perspective of an average customer with imperfect recollection and opined that the overall combination of the aforementioned elements were sufficient to make labels confusingly and deceptively similar. The SB creatively coined the term “smart copying” to describe the defendant’s attempts to highlight differences between the labels; however, it held that the overarching similarities between the two were so obvious that the dissimilarities would not matter.

- Whether the court has the relevant jurisdiction?

Though an argument on jurisdiction was raised, the SB dismissed it by observing that the defendant’s trademark application was submitted by a director residing in Delhi, and the defendant conducted business in Delhi with a godown in the city. The SB also suggested that any jurisdictional concerns could be addressed at a later stage if necessary.

- Is an injunction necessary?

The SB expressed its view that the defendant’s label was unmistakably imitative of the plaintiff’s, potentially leading to a misrepresentation that could result in passing off, and in such a case, even initial interest confusion was legally actionable. Additionally, the SB highlighted the potential for irreparable harm if the interim injunction was not issued, given the well-established presence of the plaintiff’s products in the market compared to the recent introduction of the defendant’s product under the contested labels.

Glass Half-Full, Half-Empty?

The popularity of Officer’s Choice is apparent, and its consumption has been on a rising trend for approximately a decade now. The brand’s popularity has been equally accompanied by a rather notable history of involvement in copyright litigations (discussed here, here, here, and here). This case, prima facie, appears to be a straightforward instance of trademark infringement, and the image above clearly portrays despite some minor differences, how likely it is for a reasonable person to be confused between the two. The court’s analysis here worked on the same logic and highlighted the potential confusion it may cause in the market.

However, the court’s reasoning regarding confusion raises some concerns. Consider the following excerpt from the order: “The Court must put itself in a realistic position to see how bottles were stacked on bar counters. These venues were typically not brightly lit and were usually dimly lit. In such a setting, if a consumer ordered [the] plaintiff’s product and the bartender served [the] defendant’s product, owing to the broad similarity of the labels, the consumer might not even be able to tell that the product served was that of defendant’s and not of plaintiff’s. The test was not of the standard of a connoisseur but that of an ordinary consumer or lay-person. Even the purchase at liquor outlets would include consumers who could be from varying strata of society and might not be able to discern fully the distinguishing features. Confusion as to affiliation or sponsorship was a clear possibility”.

Given that it is a well-settled principle that in trademark infringement, when assessing the resemblance between the names of the two products, the proof of actual confusion should be compelling enough to the extent that consumers find it exceedingly difficult to differentiate between the two, or are unable to do so altogether (Polaroid Corporation v. Polarad Electronic Corporation). When dealing specifically with labels and trade dresses, the Indian courts have had similar observations. In the case of Shree Nath Heritage Liquor Pvt. Ltd. v. M/s Allied Blender & Distillers Pvt. Ltd., the court noted that the marks ‘Officer’s Choice’ and ‘Collector’s Choice’ are prima-facie deceptively similar due to conveying the same meaning. It observed that despite different trade dress, consumer confusion between the two products is highly likely, given consumers’ expectation of variants from manufacturers of alcoholic beverages.

In this paragraph, however, the court explicitly makes assumptions about the locations where the products are served and the types of consumers who consume the product. The accuracy of these assumptions can undoubtedly be a matter of question, and having based the order on such ungrounded and unreasoned presumptions raises doubts about the broader precedent the court is setting.

The reasoning of the DHC becomes even more intriguing when we consider the Madhya Pradesh High Court’s rejection of Pernod Ricard’s appeal in 2023. The MPHC asserted that consumers of premium whiskey are “educated” and possess the ability to distinguish between brands, thereby finding no resemblance between ‘Blenders Pride’ and ‘London Pride.’ In the case of Pernod Ricard India Private Limited v. Karanveer Singh Chhabar, the MPHC emphasized that educated consumers of premium whiskey can easily differentiate between brands, highlighting the absence of visual, phonetic, or structural similarity in packaging and bottles. While the MPHC assumed the consumers to be educated individuals, the DHC, in this context, also makes a similar assumption but takes an alternate stance.

And DHC’s reasoning here with respect to dimly lit settings remains concerning still. The major reasoning of the court is that bottles in bars are typically in dimly lit environments, and it remains unclear whether the labels on these bottles are similar. However, why limit the presumption to bars and not extend it to liquor stores? This assumption is unsupported by sufficient reasoning by the SB. A similar approach in future cases can bring about unanticipated repercussions with courts giving out injunctions based on personal vagaries.

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- PlatoHealth. Biotech and Clinical Trials Intelligence. Access Here.

- Source: https://spicyip.com/2024/02/a-case-of-smart-copying-peace-maker-restrained-from-imitating-officers-choice.html