“Respondents acted to circumvent USPTO rules by improperly entering the name and electronic signature of deceased attorney Jeffrey Firestone…”

(from USPTO Order to Show Cause of August 25, 2022)

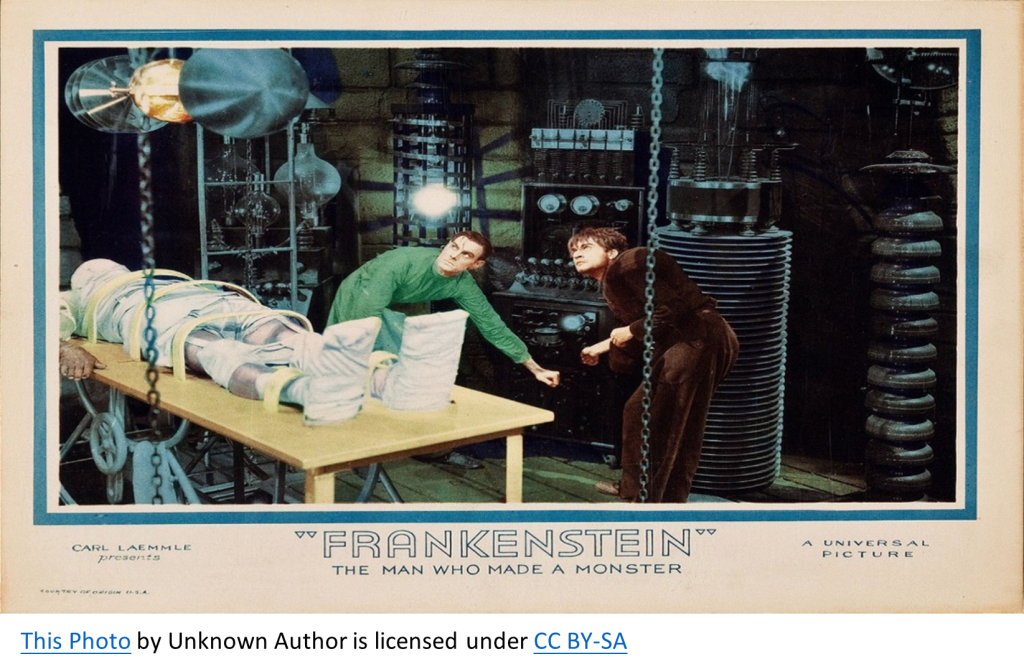

It sounds like a bad horror film from the 1950’s: “Frankenstein Trademark Agents from China.” Chinese trademark agents are now claiming that deceased US trademark agents are filing fraudulent trademarks in their names. An August 25, 2022 Order to Show Cause issued by Deputy Trademark Commissioner Amy Cotton reveals that there was indeed an attempt to revive, at least for trademark filing purposes, the name of a deceased trademark agent as the local counsel for Chinese applicants. Other forms of fraud continue. For example, lawyers who never practiced trademark law are also now being claimed as trademark agents for Chinese clients. The “resuscitated” trademark lawyers are intended to satisfy the requirements of changed PTO rules that all foreign applications must now be filed by a US-admitted trademark lawyer.

This latest case is one of several involving Chinese trademark agent malfeasance in the United States, about which I have intermittently blogged. Despite the significant sanctions being announced or imposed on the agents and applicants in such cases, in reality, the sanctions against the China-based defendants are modest. The defendants are likely to only suffer the pain of public embarrassment as well as a loss of their (unauthorized) practice before the USPTO. Clients, however, may suffer from the cancellation of fraudulent applications. To the extent that the trademark applications were subsidized by the Chinese government, there may be some additional government monetary losses. Any referral to criminal prosecution for commercial or wire fraud is not likely to result in the conviction or extradition of the China-resident party. Currently, criminal justice legal cooperation with China on transnational crimes has been suspended in the aftermath of the Nancy Pelosi visit to Taiwan. Even during happier days in bilateral relationships, I guess that these cases were unlikely to catch the attention of prosecutors from either country in light of the larger, more important cases that probably needed to be addressed by both countries.

Despite the limitations of the sanctions, PTO is to be commended for addressing these issues. I am unaware of any sanctions having been successfully imposed by state disciplinary authorities upon China-based lawyers who have practiced in the United States or appeared before US courts. The lack of enforcement is surprising. The volume of trade and trade in services with China, including exports of technology is high. There are large numbers of dual-admitted lawyers, large numbers of law firms with Chinese and US lawyers and offices or relationships in either country, and there are inherent statutory ethical conflicts in a cross-border practice involving China due to differing ethical standards. Among those conflicts are the lack of attorney-client privilege in China, ethical obligations in China in favor of the Communist Party (and not the client), restrictions on the use of the media in cases or ex-parte communications with judges in the United States, and duties of candor to an IP office in the United States Clients may also be affected. They may not well understand how these conflicts in ethical rules can affect their interests in the course of legal representation and, for example, may not be advised that communication with a US lawyer based in a China-based branch office may not be protected by attorney-client privilege.

USPTO is, however, limited in how much it can disciplinary measures affecting foreign lawyers. It is restricted by its own rules from pursuing cooperation with other bar authorities. USPTO rules permit it to “refer the existence of circumstances suggesting unauthorized practice of law to the authorities in the appropriate jurisdiction(s).” If the lawyer is legally engaged in the practice of law, but has otherwise engaged in misconduct as defined by USPTO’s rules of practice, there appears to be no specific authorization of referral to another jurisdiction. The USPTO rules do permit disciplinary proceedings at the USPTO against individuals who have been publicly disciplined in other jurisdictions under its procedures, and. I am unaware of any such request having been made of the USPTO from a Chinese authority. Moreover, given the Chinese context, this type of request may be too draconian. For example, a US patent lawyer who is also admitted in China should not be disbarred from the USPTO because he has refused to obey a request of the Communist Party of China.

As USPTO sanctions behavior before the USPTO principally through a suspension of practice or disbarment, there has been no need for a choice of law provision. With the exception of Canadian lawyers that practice before the USPTO and are subject to USPTO disciplinary actions, sanctions involving foreign lawyers would necessarily be rare. There is also no choice of law counterpart in the rules of the Office of Enrollment and Discipline to the Model Rules of Professional Responsibility, Rule 8.5, which would provide greater disciplinary authority to pursue overseas conduct that affects clients in a US jurisdiction. California Rule 8.5, for example, permits choice of law determinations based on the jurisdiction in which the lawyer’s conduct occurred, or, if the predominant effect of the conduct is in a different jurisdiction (including an overseas court case), the rules of that jurisdiction apply. California would then have jurisdiction over an individual whose actions have a predominant effect upon California. Since the USPTO sanction primarily involves an inability to appear before the USPTO, there is little need to consider a choice of law rule as the USPTO has no authority to sanction behavior that does not involve patent or trademark prosecution before it. If the matter involves a lawyer admitted before a state bar and his or her unauthorized practice of law, the matter would be referred to that state bar. This option had not been pursued by USPTO with the bar authorities in China, perhaps due to unfamiliarity with the Chinese legal landscape or a sense that it would be futile.

In a globalized IP economy, USPTO’s limited role as a disciplinary organization is arguably anachronistic. Intellectual property is now a transnational legal undertaking. USPTO needs to consider how to address unethical behavior that occurs overseas, that affects the USPTO and/or its rightsholders. Consider a hypothetical case of a USPTO-enrolled lawyer who files for a “squatted” trademark that should properly belong to an American company in China. The USPTO would have no jurisdiction over the matter, as the issue does not involve prosecution of a US-registered trademark. However, this type of behavior should be recognized as inappropriate for an IP lawyer practicing before the USPTO. If the US lawyer is publicly sanctioned by the Chinese trademark office, there is a public policy argument for reciprocal disciplinary measures, even if USPTO would not otherwise have jurisdiction over the matter. Another example might be a US lawyer resident in China who is asked to disclose information regarding a client’s licensing practices or technology by a Communist Party official. This attorney might be sanctioned in China if he did not comply with a political request of this nature, but I do not think that the lawyer should lose her US bar license. Finally, we have the example of the Frankenstein trademark agent, where living Chinese individuals, who may be China-admitted trademark agents or lawyers, are defrauding the Chinese government and Chinese applicants, as well as the USPTO. Sanctions against their ability to practice before the USPTO clearly appear inadequate.

The thousands of squatted and fraudulent trademark applications that the USPTO has discovered over the years are further evidence that the lack of disciplinary prosecution in China does not mean that there is a lack of unethical behavior by Chinese lawyers which need to be subject to broader disciplinary actions, including referrals to criminal prosecution in the US or to Chinese disciplinary authorities.

There remains a need to address cross-border behavior in IP that affects US interests, but that cannot be adequately deterred by USPTO disciplinary actions. The USPTO has already sanctioned some American lawyers who may be working with these Chinese applicants, which may have potentially imperiled the licenses of these lawyers to practice in their home jurisdiction. In addition, there have been civil cases brought in the United States against Chinese clients or Chinese-resident US counsel, alleging that unethical action was requested by the client, including in IP disputes. US courts on occasion, have also noted the existence of potentially fraudulent activities of Chinese clients or their representatives. These non-USPTO actions, as best I can determine, have generally not resulted in the imposition of sanctions.

State bar authorities have not shown an appetite thus far to bring cases against American-admitted lawyers living overseas. In an effort to determine how much the theoretical ethical conflicts facing US lawyers in China have materialized into actual bar disputes, I sent email surveys last year to all the state bar disciplinary authorities in the United States. None of the bar authorities that responded could locate any instance of cross-border disciplinary actions involving referrals to a Chinese authority or from a Chinese authority, or complaints based on conduct that originated or was undertaken in China. The general principle of US cross-border ethics compliance seems to be that “heaven is high, and the emperor is far away,” i.e., the chance of disciplinary prosecution from the United States is slim. By this standard of US state bar authorities’ prosecution of ethical violations, USPTO disciplinary action is a remarkable exception to this principle of not sanctioning overseas actors whose actions have an impact on a US tribunal or US clients.

Given current bilateral relations, the opportunity to fill the gap that exists for unscrupulous actors to flee from one jurisdiction to another is remote. If bilateral relations were to improve, it is possible that Chinese trademark authorities or the Ministry of Justice could view these requests for reciprocal discipline by the USPTO or a state bar in a favorable light. As China has cracked down on unscrupulous trademark and patent filings, both US and Chinese IP offices could find common cause in addressing these increasingly outrageous behaviors. Such forms of bilateral cooperation would be in the long-term mutual interest of both countries, which should be interested in protecting the integrity of their offices, protecting consumers from unscrupulous activities, and preventing fraudulent behavior that increasingly shocks the conscience.

- Coinsmart. Europe’s Best Bitcoin and Crypto Exchange.Click Here

- Platoblockchain. Web3 Metaverse Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- Source: https://chinaipr.com/2022/08/31/frankenstein-trademark-agents-filing-from-china/