Quick! Name the world’s largest manufacturer of personal transportation in 19th Century. If you guessed Studebaker, you’d be correct.

While never a leading manufacturer of automobiles, it was the world’s oldest personal vehicle transportation company when it when it ceased automobile manufacturing in 1966.

This week in 1852, Henry and Clement Studebaker open a blacksmith shop in South Bend, Indiana. Studebaker eventually becomes a leading manufacturer of horse-drawn wagons to the U.S. Army during the Civil War before switching to automobile production in 1902.

Yet their ties to wagonmaking date to Colonial America, bonds that few in the 20th century appreciated when the form succumbed to decades of inept management.

A car company with deep roots

No other car manufacturer has roots as deep in the history of transportation as Studebaker.

Our story of Studebaker’s long, proud history begins in Germany, where Peter Staudenbecker and his siblings, Clement, Wilhelm, Ann and Johannes, reside in Solingen, Germany, nicknamed the “City of Blades” for its numerous cutlery manufacturers.

But life isn’t going well for them in 1725, as war, taxes, and religious oppression are all taking their toll. By 1736, the Staudenbeckers are sailing for America about the Harle, a British ship heading to Philadelphia, then the world’s second-largest English-speaking city outside of London.

But in the process of preparing for their passage, an agent anglicizes their name to Studebaker. Then, before boarding, they must pledge allegiance to the British crown.

It’s a new world indeed.

Settling in the American colonies

Arriving in Philadelphia, the Studebaker clan settles in Washington County, Maryland, about 120 miles southwest of the City of Brotherly Love. They set up a wagon manufacturing business on a 1,471-acre tract, and built the county’s first bridge. A hydraulically powered mill is set up along the Conococheague Creek, which feeds into the Potomac. But unlike rivals, Peter Studebaker didn’t employ slave labor. And Studebaker was generous with employee benefits, giving employees residential deeds and land grants.

But the Studebakers are a large clan, and Peter’s grandson, John, ended up moving west to Ashland Ohio, 67 miles southwest of what would become Cleveland. There, they establish the Ashland Carriage Co., manufacturing two exclusive wagons whose names are known even today: the Prairie Schooner and the Conestoga. The former is one you’re familiar with from Western movies, with its white canvas roof. The other was designed to haul up to six tons of cargo.

The start of something big

It’s John’s sons, Henry, 26, and Clement, 21, who would head even further west to South Bend, Indiana in 1850 looking to start their own wagon company. It would take two years to raise the needed funding to establish the H&C Studebaker Wagon Co. But this week in 1852, the company opened with $68 in capital, or $1,924 when adjusted for inflation. Later that year, their brother John Mohler, 19, joined the clan as the business continued to grow.

Orders quickly began to outpace the brothers’ ability to fill them, and by 1857, they started to recruit and train workers. A fourth brother, Peter Evans, relocated to South Bend.

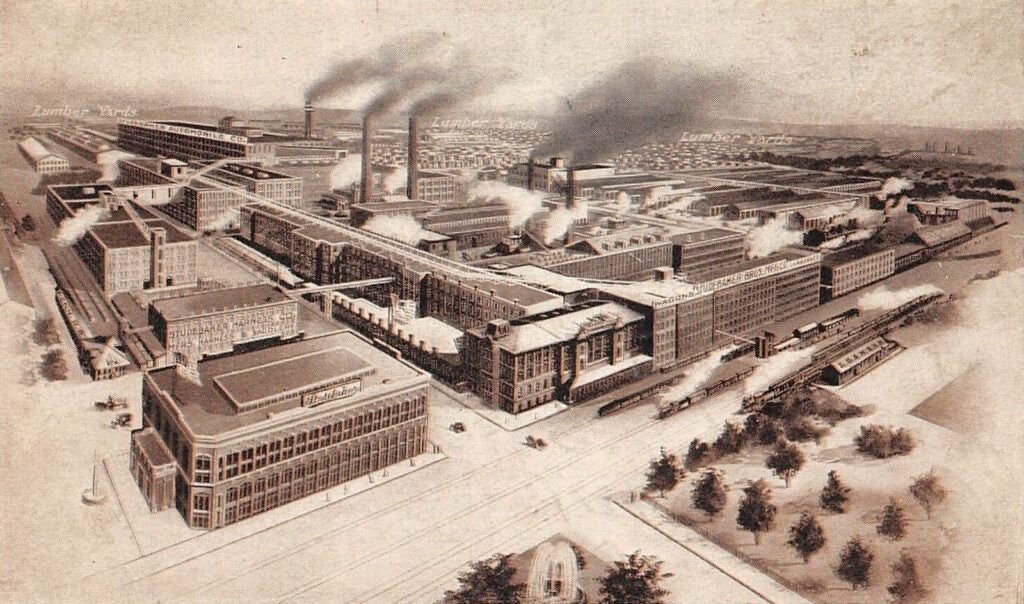

But it was the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 that would change their fortunes, as the Union Army approached the company to build wagons for the war effort. Being of the Dunkard faith, the Studebakers were and vehemently anti-war. Nevertheless, they decided to fulfill the request, which would see the company expand to 140 employees in plants that sprawled across four acres. Building some 6,000 carriages annually, total sales reached $500,000 by 1868, or $8.7 million today.

The company revamps

That same year, 1868, the company reorganizes as Studebaker Brothers Manufacturing Co., with capital of $75,000 (or $1.3 million today). Soon, showrooms were opening up nationwide, and the company would become the largest wagon manufacturer in the world, realizing sales of $1 million, or $20.7 million adjusted for inflation. Their wagons nabbed top awards at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia and the 1878 Paris Exposition.

Their reputation continued to grow, so much so that President Benjamin Harrison ordered Studebaker wagons for the White House fleet in 1889, one year after the company received orders for 500 carriages for the Spanish-American War. Sales reached $3.5 million, or $98.3 million today. But something new was coming – the automobile.

A new century and new fortunes

By now the Studebaker Brothers were the largest manufacturer of carriages in the world as well as America. And as the 1890s brought with it the first automobiles, the company builds its first prototype in 1896. But the brothers are split about its prospects as success in building wagons makes them hesitant to enter automaking.

Once they do, they choose the wrong horse: electric vehicles, beginning in 1903. The company switches to gasoline power in 1911, by which point Ford’s Model T outsells Studebaker by nearly 5-to-1.

Studebaker would never be the world’s largest transportation manufacturer again. The company would manufacture cars for most of the 20th Century, but it would remain an also-run, the largest of independent automakers, closing for good in 1966.

However, one vestige of the company survives.

In 1963, with Studebaker in financial peril, executives decide to sell its defense business, which dates to the Civil War, to Kaiser Jeep. In 1969, Kaiser Industries agrees to sell Kaiser Jeep Corp. to American Motors Corp., with Kaiser’s military division spun off as AM General, manufacturer of the Humvee.

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- Platoblockchain. Web3 Metaverse Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- Source: https://www.thedetroitbureau.com/2023/02/the-rearview-mirror-the-birth-of-studebaker/