On the recent Delhi High Court ex-parte injunction in favor of journalist Rajat Sharma against satirist Ravindra Kumar Choudhary, we are pleased to bring to you this post by SpicyIP intern Aarav Gupta, discussing the nominative fair use aspect here and the lack of interim injunction three factor assessment by the Court. Aarav is a third-year law student at National Law University, Delhi. He is passionate about geopolitics, foreign policy, international trade, and intellectual property and spends his time reading and watching sports. His previous posts can be accessed here.

Parody Under Fire: The Misuse of Ex-Parte Injunctions in Trademark Law to Curb Satire?

By Aarav Gupta

“Humour is necessary for democracy for reasons other than serving as a device for spreading the truth and attacking fools and knaves. In a free society, the populace engages in a wrenching struggle for power every few years. Humour lets us take the issues seriously without taking ourselves too seriously. If we can laugh at ourselves as we lunge for the jugular, the process loses some of its malice.”

Gutterman, New York Times Company V. Sullivan

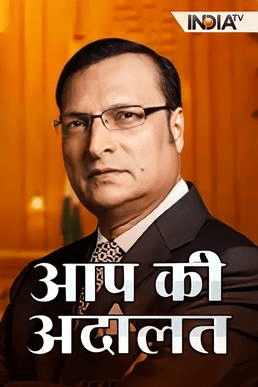

India TV, a prominent news channel and its chief editor Rajat Sharma (plaintiffs), host of a talk show, Aap Ki Adalat, were recently in the news (see here, and here,) for their trademark and personality right infringement lawsuit. In the highly publicized dispute, it was alleged that the use of phrases and marks “Jhandiya TV” and “Baap ki Adalat” by Ravindra Kumar Choudhary, a satirist, was infringing the plaintiff’s “India TV” and “Aap ki Adalat” trademarks and personality rights. Prima facie agreeing with the plaintiffs, the Delhi High Court on May 30, granted an ex-parte ad interim injunction, acknowledging infringement of Rajat Sharma’s personality rights and India TV’s trademarks/logos, albeit without making a detailed assessment of the three factors for an interim injunction.

This post aims to address the trouble that such an order has created in trademark jurisprudence and that it sets a bad precedent for satirists, creators, and anyone who wants to express dissent or commentary on famous “personalities” in general.

As a quick background before proceeding: The plaintiffs asserted that Choudhary, a “self-proclaimed political satirist,” created and shared audio video footage on social media networks. They alleged that the defendant was using a logo- “Jhandiya TV” and the mark ‘Baap Ki Adalat’ that was “deceptively similar” to IndiaTV’s logo and show ‘Aap ki Adalat’. Interestingly, while the Court did not specifically address how the impugned marks were used in a trademark sense, the use of slang phrases such as “jhand” (depressing) and “baap” (father) in the present context seems to fall under the area of parody or satire (see here and here). For instance, the similar phrase “Baap ki Adalat” has been used across different channels and in different languages by satirists. In popular culture, different slang has been ingeniously used in humorous circumstances to elicit laughter rather than bewilderment or trademark infringement. This play on words turns the original show’s serious tone into a lighthearted commentary or satire. Replicating the show’s format of running a fake court presided by a paternal figure and keeping a public figure in a witness box, in these parodies the comedians replace “Aap” (you) with “Baap” (father), and add another element of humour and satire on the type of questions generally posed by Sharma before the featured guests.

The Court, ignoring the above, ordered the sites to delete social media posts and links including the infringing trademark or logo, and instructed Sharma to send a notification to Choudhary and the sites in question.

Previous (In)Stances of/on Parody and Satire vis a vis Trademark Infringement and Personality Rights Violations

So why did the Court come down so heavily on the satirist? Ironically, the Court in its previous judgements has dealt with this issue very differently. For instance, in a case involving Jackie Shroff, the Court stated it was critical to preserve the creator’s “artistic and economic expression” beyond the actor’s personality rights. It very categorically remarked that “The format, akin to a meme, spoof, or parody, is part of a burgeoning comedic genre that leverages the cultural resonance of public figures to create engaging content. YouTubers (Who are also the defendants in this case) are a growing community, and the substantial viewership of these videos translates into significant revenue for the creators, underscoring that such content is not merely entertainment but also a vital source of livelihood for a considerable segment, particularly, the youth.” The Court in this instance has very clearly distinguished between creating parodical content and infringement of personality rights, citing the source of livelihood and earning. Read more about this order here. The order on personality rights even in the case of Amitabh Bachchan v. Rajat Nagi and Ors. excludes mimicry artists, who are protected under the right to freedom of expression.

The intention of the usage in this context, and the effect of such use in the eyes of the public all play an important part in evaluating infringement. In Tata Sons Limited v. Greenpeace International and ors., a clear explanation was given: “The relationship between the trademark and the parody is that if the parody does not take sufficiently from the original trademark, the audience will be unable to distinguish between the trademark and thus comprehend its humour. Conversely, if the parody steals too much, it may be judged unlawful since there is excess stealing and insufficient originality, regardless of how amusing the parody is.” Similarly, the Court also observed in the case of Ashutosh Dubey v. Netflix “It is a known fact that a stand-up comedian to highlight a particular point exaggerates the same to an extent that it becomes a satire and a comedy. People do not view the comments or jokes made by stand-up comedians as statements of truth but take them with a pinch of salt with the understanding that it is an exaggeration for the purposes of exposing certain ills or shortcomings.” Why the Delhi High Court has now changed its trajectory completely is something to worry about, given the reasons cited below.

The Idea of Nominative Fair Use

The idea of nominative fair use allows using a trademark if it is required to identify the product or service in question and when no other phrases can adequately describe it. Read about this in more detail here. As a type of nominative fair use, Parody uses the audience’s identification of the original trademark to convey its message. The juxtaposition and change of the original mark generate laughter and satire. In this context, “Baap ki Adalat” and “Jhandiya TV” are not traditional uses of the trademarks as under Section 30 of the Trademarks Act. “Aap ki Adalat” and “India TV,” but rather parodic allusions that should be protected under the nominative fair use theory. The doctrine of ‘nominative fair use’ is encapsulated under Section 30 of the Trade Marks Act, 1999 (“Act”), an affirmative defence available against a claim of infringement by the proprietor of a registered trademark. Specifically, normative fair use refers to the use of a trademark in a manner that does not create confusion regarding the origin of the mark and does not result in the mark being associated with the new user in any way. This includes the use of another’s trademark to identify the plaintiff’s goods or services, which is not considered infringement as long as there is no likelihood of confusion. (see Government Marketplace v. Unilex Consultants). The explanation provided here represents only one specific instance of normative fair use, similar to how parody constitutes another distinct category of normative fair use. It often refers to news, criticism, commentary, parody, comparison ads, and other non-commercial uses of registered trademarks.

Trademark law is designed to protect customers from ambiguity about the origin of products or services, as well as to preserve the trademark owner’s goodwill. However, when used to prohibit parody and satire, it is unduly employed outside the purview of the law, and the extent of trademark protection is enlarged beyond its intended purpose. Parody and satire are important components of free expression; they are frequently employed to remark on and criticise public people and organisations (paywalled). In this case, especially, the constrained terms—”Baap ki Adalat” and “Jhandiya TV”—are evident satirical riffs on the well-known shows “Aap ki Adalat” and the station “India TV”. The fundamental goal of using parodic names is not to deceive the audience into thinking that the satirist’s work is related to the original programmes, but to convey societal criticism.

Lack of Reasons in the Interim Injunction Order

In light of the above nuances, the Court must discourage the overbroad use of trademark laws as virtual gag orders. However, here the Court not only seems to skid past the above intricacies but also seems to have looked past the need for it to properly assess the critical three-factor criteria for granting an ex-parte injunction. This omission adds on to the raising questions and worries about restricting free expression. The Court granted an interim order without properly considering the key issues: prima facie case, balance of convenience, and irreparable injury. Here’s a twist: There was no immediate harm to India TV. Choudhary’s parody, “Baap Ki Adalat,” was only satire, not a danger. The balance undoubtedly leaned in favour of free expression, but the Court’s hurried ruling sent a frightening message to creators worldwide. Ex-parte injunctions are formidable instruments designed for genuine situations. This case shows how ex-parte injunctions, often used to muffle competition and trademark disputes, can be misused to stifle creativity and dissent. Courts need to tread carefully and issue well-reasoned decisions to protect the delicate balance between trademark rights and free speech. In our previous posts by Swaraj, Praharsh and Tejaswini, there is a wider discussion on the dangers of exceptional powers used to issue ex-parte injunctions.

The High Court’s injunction against the satirist essentially serves as a gag order, discouraging other satirists from participating in political commentary for fear of legal consequences. This stifling impact affects the basic rights guaranteed by democratic constitutions, such as freedom of expression and the right to criticism. The matter will be heard subsequently on October 18, 2024, and we hope that such issues are rectified by the Court in the future, and that there is a wider discussion before granting ex-parte injunctions.

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- PlatoHealth. Biotech and Clinical Trials Intelligence. Access Here.

- Source: https://spicyip.com/2024/06/parody-under-fire-the-misuse-of-ex-parte-injunctions-in-trademark-law-to-curb-satire.html