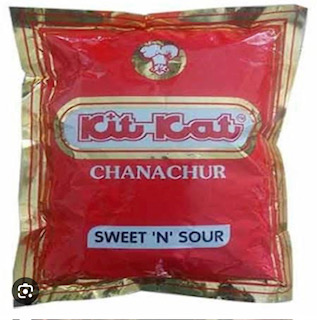

Last month, the Calcutta High Court decided a trademark dispute between KitKat (chocolate coated wafers) and KitKat (chanachur – a savoury chickpea snack) after 23 years.

For those who may not know, chanachur is a very popular street food/snack which Calcutta is famous for. Street vendors across the city make their own versions of chanachur mixed with fresh onions and spices. While chanachur can be bought from street vendors, it is also sold in packets in retail stores.

In 2000, the plaintiff, Nestle, had filed a suit for trademark and copyright infringement against the defendants, a partnership firm carrying out business from Calcutta and others.

In 2023, the Calcutta High Court permanently restrained the defendants from using their KitKat trademark and trade dress. The court relied on an IPAB decision of 2013 to come to its conclusion on trademark infringement.

Calcutta High Court decision

Nestle argued that since the IPAB had allowed its trademark application to proceed to registration while refusing registration of the defendant’s trademarks, in light of Section 124(4), the High Court was bound to rule in its favour on the question of infringement.

The IPAB had held that the plaintiff was the prior user of the trademark Kitkat having started use in 1987. The defendant’s use started four years later in 1991. This by itself was strong evidence, according to the IPAB, to show confusion. Further, it was held that the marks ‘Kit Kat’ were identical, goods were similar and travelled through similar trade channels. Also, the class of consumers being children increased the possibility of confusion. For these reasons, the plaintiff’s mark was allowed to proceed to registration and the defendant’s marks were refused registration.

The Calcutta High Court held that there was no scope to differ from these findings and on the same grounds held infringement.

Thoughts

Reliance on the IPAB order appears to be wrong both in terms of procedure and substance.

Procedure

Section 124(4) of the Trade Marks Act has to be read along with the other sub-sections of Section 124 as it forms part of a larger scheme of “stay of proceedings where the validity of registration of the trade mark is questioned”. This provision asks the court to read 124(4) along with 124(1) and 124(2). Evidently, this provision cannot be read in isolation.

Read as a whole, Section 124(4), which requires civil courts to pass orders in conformity with orders passed by the IPAB/Registrar, applies only in certain circumstances.

This provisions applies only when, in a suit for infringement, (a) the defendant pleads that the registration of the plaintiff’s mark is invalid, or (b) the plaintiff pleads that the registration of the defendant’s mark is invalid in response to a defence raised by the defendant regarding exclusive right of use due to registration.

In the current suit for trademark infringement, neither party pleaded invalidity of registration at all. The court framed 15 issues in this suit but none of them were on invalidity of either the plaintiff’s trademark registration or defendant’s trademarks.

Also, it seems like the IPAB was dealing with an opposition proceeding (which is different from a rectification proceeding) since the defendant’s mark was an application that was ultimately refused registration. Therefore, Section 124(4) did not apply in this case and the court was not bound to follow the IPAB decision.

Substance

Even if 124(4) did apply, the court was bound by the IPAB’s decision only on the issue of invalidity of registration and not on infringement. Courts have held that infringement and invalidity assessments are different (here).

Comparing pictures/words for the purpose of trademark registration is very different from comparing trademarks as they appear in the marketplace. The contexts are different and the stakes are much higher when actual shopping decisions have to be made – money is involved. Buying habits, placement of products, local retail customs, consumer psychology etc. become relevant in the context of infringement.

At the end of the day, trademark infringement turns on the likelihood of confusion which in turn depends on multiple factors. Indian courts have cited the Polaroid case which lays down various factors to be tested for assessing confusion in infringement cases. In this case, the court should have evaluated these factors and reasoned out why it gave weight to certain factors over the others. Circumstances that should have been considered:

- Strength of the plaintiff’s mark: distinctiveness and marketplace strength. While the court finds the plaintiff’s mark to be inherently distinct, an assessment of its marketplace strength has not been undertaken. Was the KitKat mark strong in relation to snacks in general or chocolates only? Is KitKat so famous for chocolates that the public would not associate KitKat with chanachur?

- Degree of similarity between the marks: in the context in which they appear in the marketplace. While the marks are phonetically identical, fonts and packaging are different. The presence of a house mark (Nestle) can reduce similarity.

- Proximity of the products: Chocolate coated wafers though related to snacks, are not the same product. While chocolates and chanachur are sold in retail stores, chanachur is likely never placed along with chocolates and is usually found along with other salty snacks like chips.

- Likelihood that the prior owner will bridge the gap: there was no evidence to show that Nestle intended to enter the chanachur market and had not done so in 23 years.

- Actual confusion: the plaintiff cited instances of actual confusion. This appears to have influenced the court’s decision. But there is no discussion regarding the amount of actual confusion that is dispositive. Is one instance of actual confusion sufficient?

- Good faith / bad faith adoption: the plaintiff was the prior user but is that enough?

- Sophistication of buyers: the court classified the consuming public to be children. There are problems with this classification – adults also eat chocolates; children are usually accompanied by adults in stores and adults make the ultimate purchase.

This apart, in a market that is filled with “rip offs”, are consumers really confused (see pictures to get a sense of the Indian marketplace where buying decisions take place)? And even if they are, what is the harm caused? Since this case took so long to decide, should the court have granted a blanket permanent injunction?

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Automotive / EVs, Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- PlatoHealth. Biotech and Clinical Trials Intelligence. Access Here.

- ChartPrime. Elevate your Trading Game with ChartPrime. Access Here.

- BlockOffsets. Modernizing Environmental Offset Ownership. Access Here.

- Source: https://spicyip.com/2023/09/have-a-break-have-a-kitkat-the-chocolate-or-chanachur.html