On February 20, 2023, the Wall Street Journal (WSJ) published an article by Stu Woo and Daniel Michaels on “China’s Newest Weapon to Nab Western Technology – Its Courts.” The article purports to document mounting discrimination against foreign patent assertions on “industries important to [China],” including “technology, pharmaceuticals and rare-earth minerals.” No experts or academics are referenced in the article.

Contrary to the many anecdotes collected by the WSJ, the published data on China’s IP environment has established that foreigners have generally fared well in IP litigation in China. Nonetheless, those conclusions are qualified by certain factors. Two of them are that foreigners are a small part of the litigation docket and that not all cases are published. Selection bias is a continuing concern.

As one example of the numerous studies that have been published, Prof. Bian Renjun estimated that the percentage of foreign-related published cases in 2014 was about 7%. The “win rate” in the overall civil patent docket for these foreign litigants was also 80%, and the injunction rate was 90%. Damages for foreign patent litigants in China, although small, were three times higher than domestic litigants. Similar data that I had collected from 2015-2019 cases, showed a foreign win rate of 79% versus a domestic win rate of 67% for invention patent assertions in the courts.

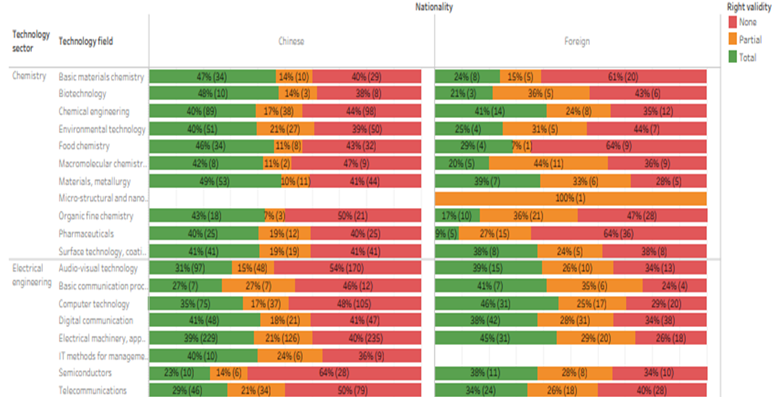

The WSJ article also discusses patent validity decisions, which is an important area of IP litigation. Data I collected from published Patent Reexamination Board (“PRB”) decisions also showed that in general foreigners and Chinese fared nearly the same if one aggregated partial and total win rates. There are, however, differences in technology areas. Notably, the partial and total win rate for foreign pharmaceutical patents was 36% compared to 59% for Chinese applicants for 2015-2019. Weaknesses in patent protection for Western pharmaceuticals are also evidenced by the limited role of the courts in linking patent protection with regulatory approval for pharmaceuticals, as required by the US-China Phase 1 Trade Agreement.

PRB cases are appealed to the Beijing IP Court as administrative cases. Total administrative cases involving patents and trademarks in 2015 were 10,926, of which 4,928 were foreign or about 45%, continuing the trend of an outsized utilization of these procedures by foreigners. Administrative cases brought by foreigners also exceeded the small number of civil cases brought by foreigners in that year (1,327). The continuing high utilization by foreigners of this docket for both patent and trademark matters has long suggested to me that litigation regarding the validity of rights is not a futile exercise. However, the outcomes from that court on patent-related disputes have not been as positive for foreigners compared to Chinese litigants. Data I had previously collected demonstrated that foreigners had a 39% win rate in invention patent cases before that court for the period 2015-2019, while domestic entities had a 50% win rate.

Another factor that affects the attractiveness of the Chinese litigation environment is the differences it maintains with the United States in patent subject matter eligibility. It continues to surprise many Americans that for over a decade, patent outcomes in China may be better than in the United States. Numerous United States court decisions have made it difficult to obtain patents in certain key technologies in the United States. The US patent office and the courts are declining to enforce a range of patents, in AI, fintech, genomics, and diagnostics. A similar problem may arise shortly if the FTC has its way in implementing a proposed ban on all non-compete agreements, including those in high-tech sectors where there is both international competition and employee poaching. Non-competes can be essential in protecting trade secrets. China, Japan, Korea, Germany, and Taiwan all enforce non-compete agreements in appropriate circumstances. It may soon be easier to enforce a non-compete agreement to protect trade secrets in China than in the United States.

The WSJ article argues that there has been a decline in IP protection in China compared to prior years to make the point that China has newly “mobilized its legal system.” The data and anecdotes in the article do not make out an overwhelming case for that proposition. There are indications that the environment is improving for both foreigners and domestic parties alike in a wide range of IP rights. For example, Emerson Electric recently won a major case in Xiamen involving a company that squatted on its trademarks. The Chinese trademark office prosecuted a trademark agency in Shenzhen that had filed 14,000 trademarks in bad faith in the United States. Companies that are found to infringe IP rights are being held accountable through a lowering of their social credit scores, which has apparently resulted in an increase in enforceable judgments. Damages for IP violations are increasing, including punitive damages. Although Western software companies have long urged the US government to address software piracy, their win rate for the period from 2006-2019 in over one thousand civil piracy cases averages over 85%. The win rate was 100% for the 63 cases brought by Microsoft. Even in less utilized areas of IP, such as plant variety protection, China has recently taken steps to incorporate leading technology practices, such as the use of molecular markers for determining infringement, to better adjudicate disputes. This should also help our own high-tech agricultural companies.

The WSJ properly identifies an issue involving Chinese courts “barring” foreign patent owners from pursuing remedies in foreign courts. These cases have all involved standardized wireless cell phone technology. The WSJ does not report that this development appears to have been arrested. Since a flurry of cases two years ago, new cases have declined or stopped. One Chinese plaintiff, Lenovo, was prohibited by a well-known Chinese judge from seeking this relief in a case against Nokia. This case decision was also placed on the website of the IP Court of the Supreme People’s Court, about fourteen months after its decision date (I discuss this case in an article on SSRN).

Although much of the data is positive, this does not mean that bias does not exist in the Chinese IP system. It also does not confirm that the use of the courts to advance industrial policy is somehow “new,” as the article suggests. Social scientists have documented potential bias against foreigners in contemporary China’s IP system, particularly in patents for standardized 5G and telecommunications technology. The wireless antenna company cases discussed in the WSJ article are also concerning because the technologies are part of wireless technology. At Berkeley Law, we have also documented declines in patent grants to foreigners for certain semiconductor technologies in recent years, which may be related to changes in industrial policy. I also discussed some very regrettable patent and employee poaching/trade secret cases involving semiconductor technology on this blog. However, the WSJ does not discuss semiconductor technology or the broad landscape of China’s efforts to reduce licensing payments for wireless phone technology.

If the WSJ wanted to make a point about declining patent protection for foreigners, a good starting point would be to determine whether counterpart patents to those that were invalidated in China were granted in other jurisdictions. This is one of several “shortcuts” to evaluating quality and non-discrimination.

A once popular TV show noted that there are “8 million stories in the naked city [of New York].” When I served as IP Attaché in China, I often met with US companies. In many cases, they encountered serious problems in protecting IP in China. In other cases, they had failed to take basic steps to protect their rights. Each story was different, time-consuming, and needed to be verified. I had to hire Chinese attorneys to help evaluate these stories. We often discovered that companies could still take action to improve their situation. One such story that I was involved in was recounted in an episode on Marketplace (Episode 900, The Stolen Company).

With a civil docket of 600,000 IP cases, there are at least 600,000 IP stories in China each year. The patent and trademark offices are also several times larger than the United States at this point in time. China also has developed the largest cadre of expert IP judges in the world who are often quite familiar with foreign practices. That’s a lot for a journalist to cover. No doubt many cases could have been better decided, and local companies or technologies were protected to the disadvantage of foreigners. In a complex environment such as China, journalists might consider testing their assumptions by consulting experts, deepening their investigations, recognizing the complexity of their arguments, and understanding the data behind the stories.

Categories: 5G, Administrative enforcement, ASI, Bian Renjun, Business Method Patent, Darts IP, empirical research, FTC, Non-Compete Agreements, Patent, patent eligibility, Pharmaceutical Patents, PRB, Software Patents, Trade Secrets

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- Platoblockchain. Web3 Metaverse Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- Source: https://chinaipr.com/2023/02/24/are-chinese-courts-out-to-nab-western-technology-an-inconclusive-wsj-article/