Following on from Niyati’s earlier post where she outlined and explained the Delhi High Court’s order in RDB and Co. HUF v. Harper Collins Publishers, we’re now very happy to bring further perspective on this case, with our former blogger Rahul Bajaj discussing the significant implications that this order brings with it. Rahul is an attorney at Ira Law.

Implications and Takeaways from Delhi High Court’s Order in RDB and Co HUF v. Harper Collins Publishers

Rahul Bajaj

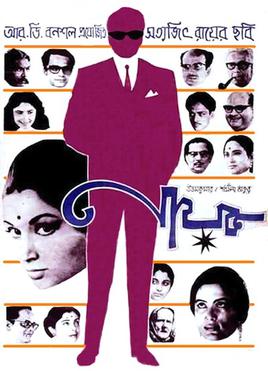

In a significant judgment delivered on 23rd May, 2023 [RDB v. Harper Collins], the Delhi High Court dealt with the vexed issue of copyright ownership in a component of a cinematographic film, namely a screenplay. At issue was the question as to whether copyright in the screenplay for the movie Nayak, is owned by the author of the screenplay, Satyajit Ray, or the producer of the film who commissioned the screenplay, R.D. Bansal [the karta of the plaintiff HUF, RDB and Co.]. Roughly in 2018, Mr. Bhaskar Chattopadhyay novelized the screenplay of Nayak. The defendant, Harper Collins, published the novel on 5th May, 2018. The plaintiff’s argument was that the novelization of the screenplay by the defendant infringed its copyright, u/s 51. The defendant argued that copyright in the film vested in Mr. Ray, and after him in his son Sandip Ray, who assigned it to the Society for the Preservation of Satyajit Ray Archives[SPSRA], from whom the defendant had secured a license to novelize the screenplay.

Holding of the Court

A breakdown of the analysis in the judgment indicates that the Court proceeded in the following steps:

- First, the definition of a literary work [S. 2(o)] in the Copyright Act, 1957 [the Act] is not exhaustive. Courts have construed literary works expansively. A screenplay is a literary work, both because it is consistent with the inclusion of ‘tables’ and compilations’ in the definition of a ‘literary work’ and because it is not a dramatic work. Therefore, a screenplay is covered by S. 13(1)(a) which vests the copyright in original literary works.

- Second, as per S. 13(4) of the Act, the copyright in a cinematograph film or a sound recording shall not affect the separate copyright in any work in respect of which or a substantial part of which is embodied in the film or sound recording. This, therefore, means that independent and autonomous copyright exists in the screenplay.

- Third, the ownership of the copyright would be governed by S. 17. The thumb rule in S. 17 is that the author of the copyrighted work is the first owner of the copyright in the work. This is subject to two caveats: [a] other provisions of the Act; and [b] the provisos to S. 17. Amongst the 5 provisos to S. 17, it was nobody’s case that the first proviso was applicable, as it applies to an individual who is employed by the proprietor of a newspaper, periodical, magazine, etc. The second proviso applies to a photograph, painting, portrait, engraving, or cinematograph film made at the instance of any person. Notably, the Court’s matter-of-fact finding that this clause was inapplicable to the case at hand as it does not cover screenplays is hugely significant, for reasons we shall discuss momentarily. The third proviso deals with work made in the course of the author‘s employment under a contract of service or apprenticeship. The Court held that this proviso was not attracted, as [a] the relationship between Bansal and Ray was not in the nature of a relationship of hire/apprenticeship; and [b] the contract was not a contract of service, as between a master and servant. At the highest, it was a contract for service, in which a service is provided in exchange for compensation. The 4th and 5th provisos cover government works and works made by international organizations and are clearly inapplicable.

- Fourth, given that S. 17 is applicable and none of the provisos was attracted, Ray was the owner of the copyright in the screenplay and therefore had the full bouquet of rights granted to a copyright owner. One such right is the right to reproduce the work in any material form. This right would subsume the right to novelize the screenplay. Therefore, the assignment of the right to novelize a screenplay by Ray’s organization was validly granted to the defendant.

Implications of the Judgment

This judgment is likely to profoundly impact the copyright licensing landscape in India. Specifically, many copyright licenses apply the work-for-hire doctrine, as per which the hiring party commissioning the work is entitled to the copyright ownership of the work. This judgment calls such arrangements into question, by clarifying that copyright ownership is entirely governed by the four corners of S. 17. By adopting a literal reading of clause b to the proviso to S. 17, and holding that it exhaustively spells out the 5 categories of works for which a work for hire arrangement is permissible, the judgment forecloses the possibility of such arrangements being entered into for any other category of work.

Practically speaking, producers of movies will now need to enter into copyright assignments to be able to claim copyright ownership in works not set out in clause b to the proviso to Section 17, such as screenplays and sound recordings. Copyright assignments are regulated by Sections 18, 19 and 19-A of the Act, so any such arrangement will have to be in conformity with the conditions spelled out in these provisions. Illustratively, as per the third proviso to S. 18(1), the author of a literary or musical work in a cinematograph film is barred from assigning or waiving the right to receive royalties or from entering into an arrangement to share the same 50-50, unless the royalties relate to communicating the work to the public or are assigned to the legal heirs of the authors or to a copyright society for collection and distribution. Similarly, as per S. 19(2), the assignment agreement must spell out the geographical scope of the assignment, opening up the possibility of geographically confined assignments being made.

Suffice it to say that licensees who had obtained rights based on the work-for-hire doctrine now face uncertainty and potential legal disputes. This judgment necessitates a re-evaluation of licensing practices and a need for greater clarity in contractual agreements.

In sum, the RDB v. Harper Collins judgment has sent ripples through the creative industry in India, challenging the established work-for-hire doctrine and raising concerns about the impact on existing licensing arrangements. The judgment’s assertion that the author of a screenplay is its copyright owner places the onus on producers to re-evaluate their rights and licensing strategies. This landmark decision calls for a careful examination of licensing agreements to ensure compliance with the evolving legal landscape. As the dust settles on the judgment, parties affected by this judgment should seek legal counsel to develop thoughtful and strategic licensing arrangements in light of this judgment.

The author would like to thank Aditya Gupta for his helpful input.

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- EVM Finance. Unified Interface for Decentralized Finance. Access Here.

- Quantum Media Group. IR/PR Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Data Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- Source: https://spicyip.com/2023/06/implications-and-takeaways-from-delhi-high-courts-order-in-rdb-and-co-huf-v-harper-collins-publishers.html