The paper, An Aviation Reduction Plan for Aotearoa, points out that aviation is the only major sector of the country’s economy currently making commitments – such as purchasing new planes and expanding airports – that are almost certain to increase emissions.

Aviation makes up a total of 12% of New Zealand’s CO2 emissions compared with the oft-cited international figure of 2 -5%.

And with aviation emissions increasing both domestically and internationally while other sectors are cutting theirs, that percentage is only going to increase.

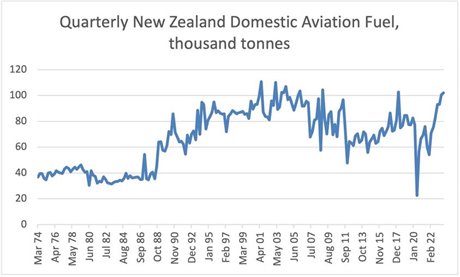

Domestic aviation emissions in the September 2023 quarter were 41% above the pre-Covid (2012-2019) average and are approaching record highs.

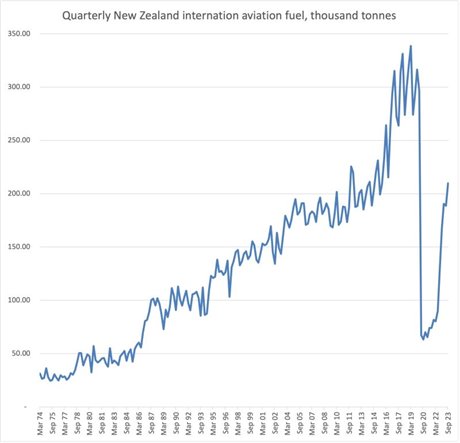

New Zealand’s consumption of aviation fuel for international flights – four times that of domestic flights – looks to be heading back to pre-covid levels.

And while New Zealand’s international flights account for the bulk of our emissions, we’re also heavy users of domestic aviation – coming in at fourth in the world for domestic per capita aviation emissions: three times higher than those of Sweden, eight times those of Finland, five times greater than the UK and a massive 45 times those of Austria.

All of those countries have more extensive and regular rail networks than New Zealand.

Professor Robert McLachlan, one of the paper’s four co-authors, says that with international aviation emissions doubling every 12 years – and no sign of that slowing down – aviation simply isn’t sustainable.

The paper identifies seven strategies for reducing New Zealand’s aviation emissions. The first of which is improved pricing.

Time to end aviation’s free ride

McLachlan says New Zealand prides itself on having a fair GST system because it applies to everything – but there’s an exception for international air tickets and domestic flights connecting to them.

“So it’s sort of outrageous that there’s this expensive, luxury item that it doesn’t apply to. On a fairness level that’s pretty inexcusable.”

The exception is due to a 1944 international convention that exempted tax on kerosene and agreed there would be no value added taxes on tickets in an effort to stimulate growth in the international aviation industry.

The paper argues it’s time to ditch the exemptions.

McLachlan says New Zealand could add a carbon price to outgoing flights “but you also want to work with other countries to get some sort of level playing field.”

Currently someone driving from Wellington to Auckland pays for the carbon via petrol and someone taking a bus or train pays GST plus their portion of the carbon charge on any fossil fuels consumed but someone flying to Auckland to catch an international flight pays no GST and the jet’s fuel isn’t taxed.

The most polluting form of transport is in effect receiving a hefty subsidy.

If GST was applied to a return ticket to Europe costing, say, $3000 it would add $450 to the cost, and if aviation was to be included in the emissions trading scheme (ETS), as proposed in the paper, with an NZU price of around $80 that would add another $240. If the non-CO2 impacts of flying (radiative forcing) were included at the same rate that would double to $480.

Adding a grand total of $930 to the price of a return ticket.

Using the same assumptions, a $600 return flight to Sydney would attract $90 in extra fees. Domestic flghts are already subject to both GST and the ETS but not the non-C02 impacts. (Radiative forcing, not specifically mentioned in the paper, would add about $8 to a return flight between Auckland and Wellington.)

McLachlan says that adding a carbon price to international airfares wouldn’t solve the problem but it would be a start.

The authors considered the idea of a frequent flyer levy – as argued for by the former chair of Air New Zealand’s sustainability advisory panel, Sir Jonathan Porritt, in Carbon News last week – but McLachlan says in the end they didn’t think it was realistic.

He says if there were no social constraints and you could wave a magic wand it would be worth considering – and could well be popular with the majority of the population which rarely flies.

About 20% of passengers are what could be called frequent flyers and they’re the ones who cause by far the most emissions.

The average New Zealander does just one and half domestic trips a year but frequent flyers are taking 20 or 30 flights annually including overseas trips.

“Current household greenhouse gas emissions are around 9 tonnes per person; for a 1.5C future these should drop to 2.5 tonnes by 2030,” McLachlan says.

Carbon budgets for aviation

A return flight to Europe clocks in at three tonnes per passenger and with aviation efficiency gains of just 1% per year there’s no way large numbers of New Zealanders can regularly take long distance flights without emitting way more CO2 per capita than is sustainable on a global level.

But New Zealand’s international aviation isn’t covered by existing carbon budgets, something the paper suggests needs to change.

It says the easiest thing to do would be do what the UK is doing and simply add it to its existing budgets. But it advises against this on the grounds that could increase carbon inequality with frequent flyers willing to bear the cost of higher airfares and crowding out other sector.

Pausing airport expansion

McLachlan says probably the single most important recommendation in the report is placing a pause on airport expansions.

“We’re really at a critical point. The Tarras airport proposal [in Central Otago]l, of course, has to be stopped. But all of the airports are planning major expansions in capacity. They’re doing this before there is an aviation emissions plan in place.

“They’re trying to jump the gun and get in while they can.”

He says there’s an urgent need for a national strategy.

Currently there is no national strategy, with individual councils deciding whether airports are allowed to expand or if new airports can be built.

Other recommendations in the report are: investment in low-carbon domestic transport options – such as inter-regional rail; public communication campaigns to encourage people to fly less, and improved emissions intensity.

What about private jets?

McLachlan says there’s not enough data to know how much private jets are contributing to emissions but his gut feeling is that it’s smaller compared to Europe and the US.

Queenstown Airport has released figures with 493 private jet movements in 2023 – a new record.

Helicopters may also contribute significantly to domestic aviation emissions, and can be a nuisance in some areas, but more research is needed, he says.

An Aviation Reduction Plan for Aotearoa, written by McLachlan, economist Paul Callister, epidemiologist Professor Alistair Woodward, and environmental sociologist Kirsty Wild ends with the following observation:

“No professor, chief executive, airline sustainability champion, or climate activist is under any illusion about the challenges involved in regulating a source of pollution. But the ICAO declaration, the ongoing Paris Agreement process, and the worsening climate crisis all point to a rapidly closing window of opportunity for genuine action on aviation. Aotearoa, as a stand-out beneficiary of aviation, has more to gain from timely and orderly action, and may also, through its State Action Plan and other diplomatic efforts, foster more coordinated global action.”

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- PlatoHealth. Biotech and Clinical Trials Intelligence. Access Here.

- Source: https://www.carbonnews.co.nz/story.asp?storyID=29750