Tag: judgment

FIFA wins in extra time: The Zurich Commercial Court upholds injunction claim against Puma

NOT EVEN TOM CRUISE. ANOTHER MISSION IMPOSSIBLE…

Pipelines versus platforms: Power and the politics of knowledge

I see three patterns unfolding:

- the widening circles of human catastrophe from large changes in water and carbon cycling

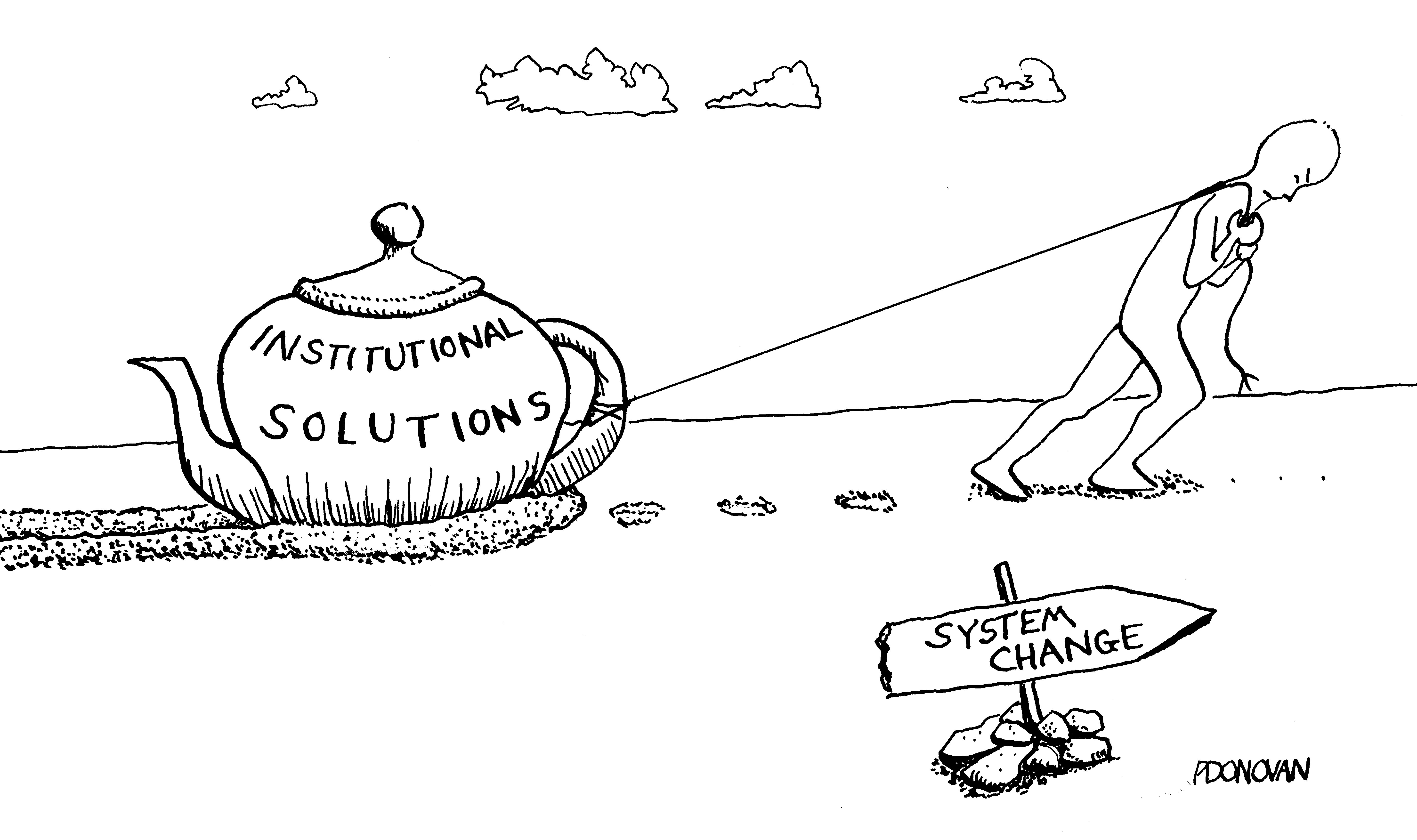

- the widening failures of institutional solutions for these challenges

- the widening movement in agriculture and natural resource management toward peer-to-peer, participatory, local learning groups.

Is the age of miracle cures--of quick fixes, of institutional, top-down solutions for complex problems--on its way out? What patterns or possibilities are these widening ripples generating?

For agriculture in the U.S., the miracle cures of the 20th century include mechanization, pesticides, nitrogen fertilizer, large irrigation projects, biotechnology, and the development of a distribution system for these technologies. These revolutionized agricultural production around the world, with a singular focus on yields and efficiency. Agricultural research and extension, along with the land-grant university system in the U.S. that trains agronomists almost everywhere, effectively created a monopoly on the creation and distribution of knowledge. Huge corporations such as Monsanto-Bayer, Syngenta, and Cargill came to control inputs such as seeds and chemicals, agricultural methods, and marketing. Many agricultural lenders followed suit. These corporations also funded a good deal of agricultural research.

There have been great successes with many of these miracle cures and short-term fixes, and even today they are continuing. They have forestalled famines, reduced pest pressure in some cases, and saved farms from failure. They have enabled some countries to feed the world by exporting cheap food, extending their technology pipelines, and concentrating profit and power for the input sectors such as machinery, equipment, fertilizer, seed, and chemicals. They have helped maintain amazingly high levels of production on degraded and degrading soils, with increasing drought and pest pressure.

The oft-used analogy here is that of a pipeline, where research and development creates innovations and technologies which are then delivered to "end users" or farmers via channels and programs that provide information and incentives for adoption. It is a one-way flow, from the creators and developers of knowledge and technology to the presumed end users, driven by carrots and sticks (external motivations). The metric for success is the rate of flow: the adoption of practices or technologies, the signups to incentive programs, the sale of inputs.

In complex domains such as ecosystems, the one-way pipeline design lacks good feedback or accountability. Researchers, input suppliers, and extension take charge of knowing, while farmers are responsible for doing. Knowing and doing are thus poorly correlated. The practices and strategies the one-way pipeline has delivered produce long-term, cascading failures: large-scale damage to soil health, desertification and compaction, massive loss of biodiversity, increased risk of erosion, drought, fire, and flood, much higher input costs, water quality issues and algal blooms, declining food quality, disappearing aquifers, more virulent weeds and pests, rising risks to human health, farm failure and consolidation, social conflict, and the hollowing out of many rural communities.

Institutional responses to these problems in the U.S. include adding different nozzles and channels to the pipeline: programs to promote conservation, sustainable agriculture, and climate-smart agriculture, to help underserved producers, to idle marginal and erodible land, crop insurance subsidies to de-risk agricultural production on increasingly degraded soils in a changing climate, to address marketing and rural community issues, for farmer mental health issues, and for institutional research on all of this.

There is also competition. Heretics and innovators have long challenged the monopoly of the USDA-land grant university axis for example on the creation and dissemination of knowledge and advice. The default or self-evident way to promote change is to set up another one-way pipeline through which an organization or consultancy can deliver its knowledge, information, best practices, and advocacy to its constituents. (See Deborah Frieze's trenchant critique and alternatives here.)

The Big Ag pipelines are still operating but there is increasing competition from sustainable, organic, or soil health movements and pipelines, which also compete with each other. Resistance and competition take many forms, including funding research to show that a rival movement's innovations don't work or can't be implemented, co-opting a movement's claims, various shades of greenwashing, and even partnership or combination.

Some heretics and innovators catalyze relationships between farmers, where similarly inclined or inspired farmers or ranchers begin to learn from each other, while still depending on pipelines for information, advice, or access to programs. This is the third pattern that is unfolding: the widening movement toward farmer-centered, peer-to-peer learning groups. This has been occurring for a long time, but in the last century the aforementioned institutional pipelines have displaced or sidelined a good deal of this activity.

Improving the productivity and soil health of a pasture or field is a complex challenge. As you might change the course of a fast-running stream by placing a log or rock in it, so the flow of sunlight energy through the pasture--photosynthesis, water cycling--means that small changes might produce large effects over time. Cause and effect may be entangled, like the chicken and the egg. There are lots of interacting variables, lots of unknowns, and some unknown unknowns.

For knowing and doing, results and actions, to become correlated, the doers must also want to know--to accept the responsibility for their own education. This happens when farmers, ranchers, or land managers realize that there is a gap or discrepancy between their present situation, and what they recognize as needed, wanted, and possible. This gap can become a creative tension, an intrinsic motivation for learning that differs from the extrinsic motivations (carrots, sticks, and judgment) relied on by one-way pipelines.

While few seem to be abandoning the pipelines, the increasing popularity of farmer-to-farmer learning groups highlights the tension between top-down and bottom-up, between one-way pipelines and the must-have accountability of connected knowing/doing. Pipelines are still where the money and jobs are for educators, marketers, and consultants, and many farmers are either loyal, dependent, or both. Taking responsibility for your own learning in the face of complex challenges is scary and hard. Peer support is not everywhere to be found, and can be difficult to create and maintain. But a possible future pattern might be represented thus:

Aggregation has occurred, analogous to a process of soil aggregation. An institution (still somewhat rectangular) is now a participant in a learning network, with two-way exchange and internal accountability/feedback like the others--who may be individuals, or local groups of individuals. Internal accountability, the entanglement of knowing and doing at multiple scales, power sharing, the participatory co-creation of knowledge, as well as semi-permeable membranes that help protect against perverse incentives, are characteristic. It resembles an interdependent ecosystem.

Such ecosystems are unlikely to be created by policy, but their evolution could be supported where there is some kind of start. Some organizations and institutions are trying to support peer-to-peer farmer networks, but there often remains a subtle collaboration between their own habits, skills, and capacities on the one hand, and on the other the trained expectations of many farmers to be told best practices, to respond to carrots and sticks, to be judged by experts. The power and acclaim that expert status confers continues to be addicting. The result is that people can postpone taking responsibility for their own learning. Knowing and doing remain separated, and monitoring or science is outsourced.

We're in the midst of an evolution, for which effective shortcuts are unlikely to appear. Three elements that can support the connection between knowing and doing in the face of complex challenges:

- Group facilitation that is knowledgeable about the local situation, but sufficiently detached so that people can take responsibility for their own learning, their own progress. Facilitators learn to be a guide on the side, not the sage on the stage.

- Questions, including questions about evidence and trend in land function, that are relevant to people's intrinsic motivations, what they truly care about. Participants can pose their own questions, as well as methods of answering them.

- An adaptable platform or framework (not a one-way pipeline!) for participatory community science that respects trust, relationships, locality, and the needs and goals of participants, and supplies a way of fostering a shared intelligence, a group memory, evidence including some detailed answers to some key questions, and a semi-permeable membrane for sharing. This is the design of soilhealth.app.

Institutional solutions . . . necessarily fail to solve the problems to which they are addressed because, by definition, they cannot consider the real causes. The only real, practical, hope-giving way to remedy the fragmentation that is the disease of the modern spirit is a small and humble way---a way that a government or agency or organization or institution will never think of, though a person may think of it: one must begin in one's own life the private solutions that can only in turn become public solutions. (Wendell Berry, The Unsettling of America, 1977)

Some further reading:

The Global Alliance for the Future of Food, a consortium of NGOs, has put out an excellent document called The Politics of Knowledge. Vijay Kumar from Andhra Pradesh was among the contributors. It calls for "participatory, transdisciplinary research and action agendas," and offers many insights into the tension between bottom-up, farmer-centered learning efforts, and the top-down pipelines that have sometimes sought to suppress or negate them.

Agroecology requires an approach to knowledge that transcends compartmentalized, reductionist, market-led, and elitist knowledge systems in favour of bottom-up, people-led, holistic, and transdisciplinary approaches to knowledge and wisdom.

The co-creation, exchange, and mobilization of knowledge and evidence creates new entry points to systemic transformation and needs to be harnessed to facilitate action across food systems. Evidence on its own does not catalyze change due to structural barriers, such as short-term thinking, cheap food, export orientation, and narrow measures of success, that keep industrial food systems locked in place. Unlocking these structural barriers requires changing our research, education, and innovation systems.

There are pdf and multimedia versions in English, Spanish, French here:

https://futureoffood.org/insights/the-politics-of-knowledge-compendium/

See also

High Court’s Failure Exposes the Festering Eligibility Sore in Australia’s Patent Laws

The Carbon Footprint Impact on Brand Image

List of the world’s top female futurists (Update #5)

Eligibility of Computer-Implemented Inventions Behind Unprecedented Numbers of Patent Office Rulings

The Pushmi-Pullyu of Chinese Anti-Suit Injunctions and Antitrust in SEP Licensing

How Reliable Blockchain Security Is [A Crypto Investor’s Guide]

Aristocrat’s EGM Inventions Set for Showdown in the High Court

What I learned from the Soil Carbon Challenge

This nonprofit organization, the Soil Carbon Coalition, was inspired in part by Allan Yeomans's 2005 book, Priority One: Together we can beat global warming, which Abe Collins and I had been reading. Yeomans suggested that increased soil carbon could make a difference for climate. In 2007 Joel Brown of the NRCS gave a talk in Albuquerque in which he said that according to the published literature, good management by land stewards did not result in soil carbon increase, and that it was too difficult to measure anyhow. With that, I resolved to begin measuring soil carbon change on ranches and farms that were consciously aiming at greater soil health.

I had done plenty of reporting on land stewardship and plenty of rangeland monitoring. I studied research-grade, repeatable soil sampling and analysis methods and combined them with some rangeland transect methods I had learned from Charley Orchard of Land EKG. In 2011 I bought an old schoolbus, made it into living quarters, and for most of the next decade I traveled North America slowly, putting in hundreds of baseline transects and carbon measuring sites mainly on ranching operations that had some association with holistic planned grazing. I resampled over a hundred at intervals of 3-8 years. The question I was asking was: Where, when, and with whose management, was soil carbon changing over intervals of several years? I called this project the Soil Carbon Challenge.

A lot of data accumulated. What did it show, what did it mean?

In order for there to be meaning or learning, there needs to be a context, a purpose. My purpose in embarking on this project, the question behind the question, was 1) to see if measuring soil carbon change over time could provide relevant feedback or guidance to land stewards who were interested in soil health, and 2) to see what soil carbon change, if it were significant and widespread, might imply for climate policy that was narrowly focused on more technical rather than biological solutions. Everywhere I traveled, water was the main issue for people, whether it was floods or drought. I measured soil carbon because it was central to the flow of sunlight energy through soils, critically influential for soil function, and easier to measure change than measuring soil water. At no point did I advocate for the commodification of soil carbon into credit or offset schemes.

The soil carbon change data that I got on resampling baseline plots was noisy and variable, especially in the top layers (0-10 cm depth). There were some pockets of consistent change, such as a group of graziers in southeast Saskatchewan showing substantial increases, even down to the 40 cm depth that I often sampled to. But the majority of change data that I collected did not offer solid support to the hypothesis that holistic planned grazing or no-till, for example, in a few years would increase soil carbon in every circumstance or locale, or that soil carbon would faithfully reflect changes in forage production, soil cover, or diversity.

Many of the people on whose ranches I sampled did not know what to do with the data or results, or simply interpreted the data as a judgment: a high or increasing level of soil carbon indicated good management, and low or decreasing was bad. Measured soil carbon change, especially at one or two points, was not meaningful, useful, or in some cases timely feedback, and may not have contributed much to their learning and decision making as I had hoped it might. For the most part the ranches I sampled on were widely scattered, and there was little interaction between them or mutual support, little opportunity for discussion or the development of a shared intelligence or a community of practice. The "competition" framing or context that I suggested in 2010 did not help. The effort tended toward an information pipeline rather than a platform that enabled people to take responsibility for their own learning. For a while I posted the data on this website, but that did little to foster discussion or interpretation, or encourage people to add learning to judgment.

Nor did the noisiness and variability of the data I collected offer solid support for soil carbon increase as a strategy for reducing atmospheric carbon dioxide and easing climate change--a strategy that was growing increasingly popular, with many people and organizations advocating for it, and which has resulted in new programs, policies, and markets to try and reward ranchers and farmers for increases (usually modeled rather than measured) in soil carbon.

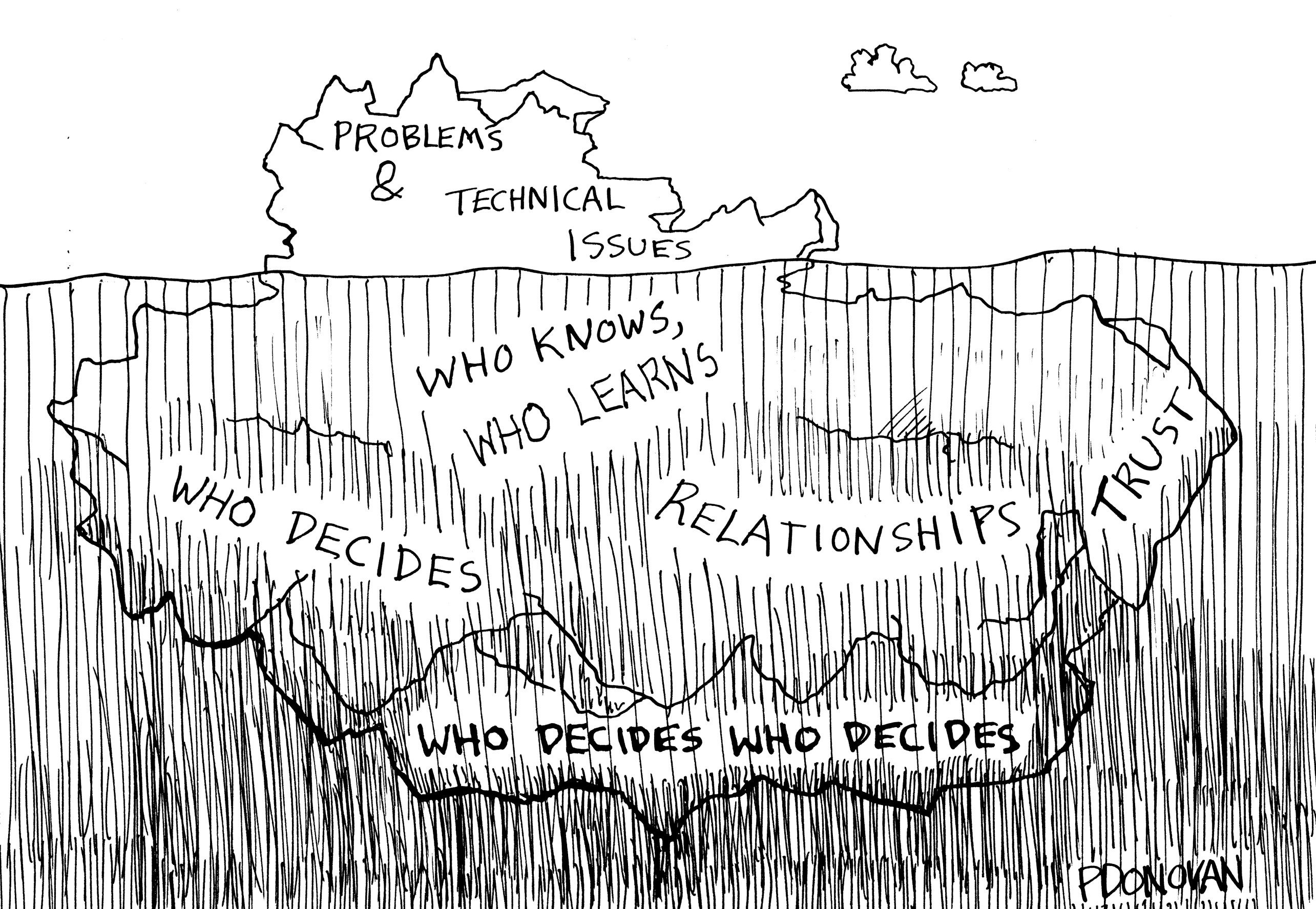

So the Soil Carbon Challenge was at least a partial failure, in that it took aim at the problems and technical issues at the tip of the iceberg, and fostered judgment more than learning and new questions. I did take some lessons from this decade of travel, conversations, workshops, transects and soil sampling, sample processing and analysis, data entry, and associated reading and research into the history of the discovery of the carbon cycle, water cycle, and climate issues. Some of these lessons resonated with what I had learned, and then forgotten, in the trainings I took in holistic management and consensus building in the 1990s.

Like many attempts at "solutioneering" the problems of soil health and climate, the Soil Carbon Challenge focused on the tip or immediately visible portion of the "iceberg," and was not designed around the center of gravity: human or people issues, paradigms and power, relationships and trust.

What I learned (or saw from a new perspective, or rediscovered):

1. Energy is a context for all life

and energy flow, from sunlight, is a pattern that connects all knowledge and activity. However, energy is an abstraction: we can only know it, sense it, or measure it by its results, the work it does, the changes it creates. Our planet is an open system largely run by sunlight energy. As I wrote here, "We are riding an enormous, incredibly complex, fractal eddying flow of sunlight energy used in many ways by interrelated communities of self-motivated living organisms whose metabolisms, behaviors, and relationships are increasingly influenced by our own." And, as Selman Waksman, Aldo Leopold, and others realized, soil is a major hub for sunlight energy flow.

2. Learning networks

are a context for the emergence of a community of practice, of a shared intelligence. These are social groupings where people share what they are learning, and are able to witness or share in the learning of others, and so gain an enriched perspective, with dialogue. It helps if these are participatory, ongoing, local, and include evidence as well as new questions. Some degree if trust is needed in order for judgments to ripen into learning, and listening is a key ingredient. Over the past year or so I have developed soilhealth.app as a way of supporting learning networks around soil health and sunlight energy flow, and am seeking partnerships on that project.

It's not that measuring soil carbon is a bad or useless thing, but a good context or purpose is needed. We learn from differences. Here are 4 suggestions for learning, about different kinds of differences, all of which may surprise and spark your curiosity:

- To learn more about flows of sunlight energy, get an infrared heat gun ($15 and up) that measures or estimates radiant heat, and begin playing with it, pointing it at various stages of sky, soil, plants, and other surfaces and objects.

- Use infiltration rings to gauge how well water infiltrates into various soil surfaces. Remember that soil moisture held in soil pores represents a huge capture of free sunlight energy.

- Record change over time in some kind of indicator, quantity, or measurement you are interested in or curious about. Precipitation or infiltration for example. For ranchers, animal days of grazing on a particular pasture for example, or pounds of gain. Repeatable observations need some kind of recording system.

- Share your observations and learning with others in a learning network. As two eyes helps you see depth, so do multiple perspectives enrich and deepen your learning.